It was great to be back at the IOE for Pedagoo London 2014, and many thanks must go to @hgaldinoshea & @kevbartle for organising such a wonderful (and free!) event. As ever there’s never enough time to talk to everyone I wanted to talk to, but I particularly enjoyed Jo Facer’s workshop on cultural literacy and Harry Fletcher-Wood’s attempt to stretch a military metaphor to provide a model for teacher improvement. As I was presenting last I found myself unable to concentrate during Rachel Steven’s REALLY INTERESTING talk on Lesson Study and returned to the room in which I would be presenting to catch the end of Kev Bartle’s fascinating discussion of a Taxonomy of Errors.

If you’ve been following the blog you may be aware that I’ve been pursuing the idea that learning is invisible and that attempts to demonstrate it in the classroom may be fundamentally flawed. Clearly, what with all the reading and thinking I’m putting in to this line of inquiry, I think I’m right. But then, so do we all. No teacher would ever choosing to do something they believed to be wrong just because they were told to, would they?

You are wrong!

The starting point for my presentation was to address the fact that we’re all wrong, all the time, about almost everything. This is a universal phenomenon: to err is human. But we only really believe that applies to everyone else, don’t we? I began by posting this question: How can we trust when our perception is accurate and when it’s not?

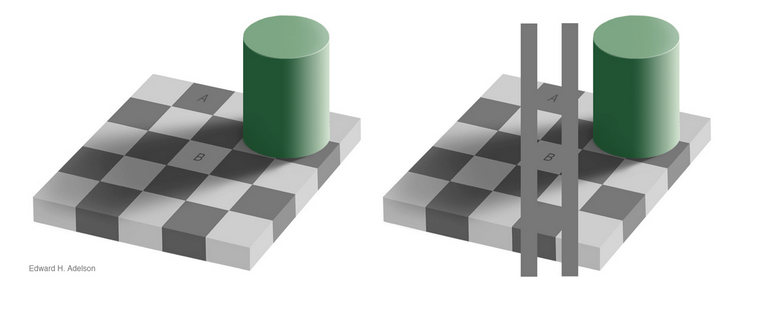

Worryingly, we cannot. Take a look at this picture

Contrary to the evidence of our eyes, the squares labelled A and B are exactly the same shade of grey. That’s insane, right? Obviously they’re a different shade. We know because we can clearly see they’re a different shade. Anyone claiming otherwise is an idiot.

Well, no. As this second illustration shows, the shades really are the same shade.

How can this be so? Our brains know A is dark and B is light, so therefore we edit out the effects of the shadow cast by the green cylinder and compensate for the limitations of our eyes. We literally see something that isn’t there. This is a common phenomenon and Katherine Schultz describes illusions as “a gateway drug to humility” because they teach us what it is like to confront the fact that we are wrong in a non-threatening way.

How can this be so? Our brains know A is dark and B is light, so therefore we edit out the effects of the shadow cast by the green cylinder and compensate for the limitations of our eyes. We literally see something that isn’t there. This is a common phenomenon and Katherine Schultz describes illusions as “a gateway drug to humility” because they teach us what it is like to confront the fact that we are wrong in a non-threatening way.

Watch this video can count the number of completed passes made by players wearing white T-shirts. Try to ignore the players wearing black T-shirts.

How many passes did you count? The answer is 16, but did you see the gorilla?

Daniel Simons and Christopher Chabris’s research into ‘inattention blindness’ reveals a similar capacity for wrongness. Their experiment, the Invisible Gorilla, has become famous. If you’ve not seen it before, it can be startling: just under 50% of people fail to see the gorilla. And if you’d seen it before, did you notice one of the black T-shirted players leave the stage? You did? Did you also see the curtain change from red to gold? Vanishingly few people see all these things. And practically no one sees them all and still manages to count the passes!

Intuitively we don’t believe that almost half the people who first see that clip would fail to see a man in a gorilla suit walk on stage and beat his chest for a full nine seconds. But we are wrong.

But it’s not usually so simple to spot where we go wrong. Our brains are incredibly skilled at protecting us from the uncomfortable sensation of being wrong. There’s a whole host of cognitive oddities that prevent us from seeing the truth. Here are just a few:

- Confirmation bias – the fact that we seek out only that which confirms what we already believe

- The Illusion of Asymmetric Insight – the belief that though our perceptions of others are accurate and insightful, their perceptions of us are shallow and illogical. This asymmetry becomes more stark when we are part of a group. We progressive see clearly the flaws in traditionalist arguments, but they, poor saps, don’t understand the sophistication of our arguments.

- The Backfire Effect – the fact that when confronted with evidence contrary to our beliefs we will rationalise our mistakes even more strongly

- Sunk Cost Fallacy – the irrational response to having wasted time effort or money: I’ve committed this much, so I must continue or it will have been a waste. I spent all this time training my pupils to work in groups so they’re damn well going to work in groups, and damn the evidence!

- The Anchoring Effect – the fact that we are incredibly suggestible and base our decisions and beliefs on what we have been told, whether or not it makes sense. Retailers are expert at gulling us, and so are certain education consultants.

Interesting as this may be, what’s the point? Well, here are just a few of the things we’ve been told are true that may not be:

- You can see learning

- Improving pupils’ performance is the best way to get them to learn

- Outstanding lessons are a good thing

- Feedback is always good

- AfL is great

I’ve discussed each of these before, so if you’re interested, please do click the links. And if you’re not interested, maybe you’re a victim of cognitive bias 😉

These though, are my cautious suggestions:

- Abandon the Cult of Outstanding

- Be careful about how we give feedback

- Introduce ‘desirable difficulties’

- Question all your assumptions – be prepared to ‘murder your darlings

But hey, I’m might be wrong.

The most important message is that as long as we stay open to the possibility that we might be wrong and remain mindful of cognitive bias, we might have a chance of not being too wrong.

Slide 6 warns against confirmation bias, but I like what I read because it rings true to my experiences! Any chance there will be a full transcript of your talk?

[…] Read more on The Learning Spy… […]

Ta dah!

I would also add ‘Thinking Fast and Slow’ by Daniel Kahnemann is also another fantastic book on the same theme, I would urge you to read it also.

My only worry is one about ‘Study – Test, Test, Test – Test’ – how does this improve understanding as opposed to improving performance? Surely it only improves retrieval strengh and not storage strength?

However, everything else you talk about is bang on the money.

I’ve had Kahnemann on the bedside table for months – must get round to reading.

Not so on the testing effect: there’s lots of research which shows that testing improves long term retrieval and transfer (i.e. storage strength) Here’s a good place to start: http://ict.usc.edu/pubs/Unsuccessful%20retrieval%20attempts%20enhance%20subsequent%20learning.pdf

Thank you for the link, I’m an avid follow of Bjork but I was under the impression that the test route only increases performance, not understanding, and given what Bjork says about ‘perfomance and learning’ I had difficulty in resolving these ideas.

[…] Everything we’ve been told about teaching is wrong, and what to do about it! Chasing our tails – is AfL all it’s cracked up to be? AfL: cargo cult teaching Questions that matter: method vs practice? […]

[…] and David Didau @learningspy was presenting about how we are wrong about everything all the time. You can read about it more here. One of the people he talks about is Robert Bjork and he has some interesting things to say about […]

You ALWAYS make me think, David – thank you! And good to meet you in the Jo Facer session. Hope perhaps to hear you speak next time.

I’m glad someone of your profile is noticing these things. Some colleagues and I have been arguing this locally for a year or more, but nobody wants to know – which rather proves the point! I would recommend dipping into ‘The Art of Thinking Clearly’ by Rolf Dobelli for more on cognitive biases, and ‘Willful Blindness’ by Margaret Heffernan for more on how this can catastrophically distort institutional decision-making.

And I’m glad someone is starting to debunk some of the myths that have made my professional life a hundred times more difficult than it needed to have been over the last decade. Thanks.

Many thanks – I’ve give the books you recommend a punt.

Anything else you think I should be debunking?

I think there are enough specifics to be going on with for now! There’s quite a lot more debunking required before these views become known more widely, I think. I think the spurious ‘causality’ between teaching and learning is fertile ground, though. I have quite a lot more reading on my own blog if you don’t already know it: http://ijstock.wordpress.com/ I found Affluenza and Obliquity particularly thought-provoking.

Ooh! That sounds ace! I found your blog last week – impressed with the posts I’ve read. Any you’d particularly point me towards?

Thanks – very glad you like it. If you can bear with me, I’m trying to put all the key points to date into one summary. I’ve piled so much in there that I’ll have to go back and think, when I’ve got a moment. In the meantime, you might find my adventures in Switzerland an interesting contrast – three consecutive starting with The Boy outside the Bubble. I’ll get back to you with another digest in the next day or two if you’d like.

Can I offer you these three…?

http://ijstock.wordpress.com/2013/12/03/mere-anecdote/

http://ijstock.wordpress.com/2013/12/07/groucho-was-right/

http://ijstock.wordpress.com/2014/02/02/blame-it-on-adam-smith/

Fascinating as ever.

[…] we are wrong more often than we’d care to admit. (David Didau has written eloquently about it here and here, and I’d strongly advise everyone to read those […]

[…] difficult – why it’s better to make learning harder Everything we’ve been told about teaching is wrong and what to do about it The Cult of Outstanding: the problem with ‘outstanding’ […]

[…] Cult of Outstanding Everything we’ve been told about teaching is wrong and what to do about it! Testing & assessment: have we been doing the right things for the wrong […]

[…] can read David’s original post following Pedagoo London 2014 here. I’ve also included links within this post to lots of other posts David has written that […]

[…] true. Why bother testing the efficacy of something we can ‘see’ working? Well, as I’ve pointed out before, we are all victims of powerful cognitive biases which prevent us from acknowledging that we might […]

[…] self evidently true. Why bother testing the efficacy of something we can ‘see’ working? Well, as I’ve pointed out before, we are all victims of powerful cognitive biases which prevent us from acknowledging that we might […]

[…] Because our brains work in very similar ways, we all have the tendency to fall victim to the same cognitive biases. Possibly part of the appeal is that we want to believe our failure to learn is due to teachers […]

[…] think too much about the possibility that we might be mistaken stems in part from a whole suite of well documented cognitive biases, but also arises from institutional pressures. Schools put pressure on teachers to explain away […]

[…] evidence according to their prejudices. I’ve outlined the problems with cognitive bias here, but for a more extensive analysis, you might find my book What If Everything You Knew About […]