My eldest daughter is in Year 6 and applications for secondary school applications need to be in by the end of October. To my shame, I’ve taken the route my middle-class parents take; we’re moving into the catchment of the school of our choice. But why have we chosen it? Well, the results are very good; the view of parents is overwhelmingly positive; it offers about the right blend of academic and ‘creative’ subjects, and it has the kind of ethos that chimes with our values. I think. But I don’t really know. I’m basing these judgements on league tables, Ofsted reports, word of mouth and gut instinct.

Choosing a school can be an agonising process. Ever since I wrote about my visit to King Solomon Academy a few weeks ago and left the question of whether I’d want my children to go there hanging, I’ve been seriously thinking about what my ideal school might be. And today I might just have found it. Sadly it’s in Warrington and I’m in North Somerset. I think we’re probably just outside the catchment. The school is Kings Leadership Academy in Warrington, and at first glance it’s an unprepossessing site:

Although it’s in to its third year operation, it won’t move into a permanent building until June next year. Principal, Shane Ierston and Chief Executive, Sir Iain Hall (co-founder of Future Leaders) took time out of their busy schedule to talk me through the underpinning philosophy and show off a school of which they are rightly proud.

So what is it that makes me want to send my children there? This is a hard thing to nail down and for doubters it’ll take the proof of external exam results to verify that this particular pudding is worth eating. Taken individually, its parts perhaps don’t adequately illustrate the whole, but I’ll try to unpick what King’s does that makes it special. Like KSA, King’s is inspired by the US charter school movement, but they have consciously rejected the structure and feel of KIPP and instead tried to emulate the North Star model. (They were quite dismissive of “all that clicking”.) I hadn’t been aware of much of a difference, but apparently there is. That difference is a focus on developing character.

Character education is like Blackpool rock, it runs through the core of everything we do at the school.

Sir Iain Hall

I’ve always been a little sceptical about this as a stated aim of schooling but I have to say, I’m a convert. King’s use the ASPIRE code to talk about character and it informs everything they do.

Most schools have something similar, but here it seem to be more than just words. These values permeate the classrooms and corridors as much as they do the head’s office. When I talked to pupils they were clear on the value of the ASPIRE code and were able to relate it to their lives and lessons.

There are some aspects of school life that a jarringly different to ‘normal’ schools. Pupils hand in homework to a homework monitor at the beginning of the school day; school begins with every pupil reading in silence in the hall; all pupils line up together in silence before lessons; teachers shake hands with pupils on their way in and out of lessons; pupils chant the school motto before lessons. And they have a school song.

All this may sound a little stifling but, despite the order and calm, King’s is the least stifling school I have ever been in. Lessons are purposeful, but relaxed and children were evidently enjoying themselves. Sir Iain talked about their belief that structure leads to freedom and the school provides the ordered framework for children to “find themselves”. There’s a similar tension at work in the schools bid to ‘make’ teachers creative: certain routines are imposed so that the teacher can “be themselves”. In the science lesson I saw, pupils were working in groups to draw diagrams of atoms on wall-mounted whiteboards before comparing and critiquing each other’s work. The teacher expertly probed answers to get at underlying misconceptions and unearth different perspectives. I had thought he hadn’t gone far enough, but on discussing the lesson later I discovered this Year 7 class were a ‘nurture’ group working a level 3 and below. To say I was surprised is an understatement. Nothing in their behaviour or in their contributions to the lesson had prepared me for this and I’d assumed they were as able as any other pupils I’d met. And this is the point: because staff have such high expectations, pupils rise to them.

The school’s USP though is the emphasis on leadership. Pupils are trained to become ‘young leaders’ and taught a bespoke leadership curriculum accredited by the Royal Chartered Management Institute. This sounds all very well, but does it actually make any difference?

During lunch I met with the Student Parliament and discussed their view of the school. They were unanimously positive and enthusiastic, pointing out the differences with their previous schools where disruption and low expectations were the norm. In some senses they were pretty typical of the kind of kids you find of student councils at any school: serious, geeky and prone to bullying. I asked them how they were treated by other pupils and, quite seriously, they told me how they were respected and how other pupils looked up to them. I asked them what happened when pupils failed to conform and they dutifully explained the behaviour system. The ultimate sanction is to be put in isolation and Shane later told me that they hadn’t had a single fixed-term exclusion in the 3 years the school has been open. So what happens to the kids that get put in isolation? Well, apparently they have to issue a public apology in front of the whole and ask permission to go back into lessons from their peers! The parliament interrogate the miscreant before voting on whether to allow them back or keep them in isolation.

- Me: (a bit taken aback) So does this happen a lot?

- Parliament leader: It happened once last year and we voted to let the boy back into lessons.

- Me: And how’s he been since?

- Parliament leader: Fine. He’s now working hard and behaving properly.

That just ain’t normal. But it’s kinda cool.

One of the parliament members told me how shy he’d been when he started in Year 7. He’d been a school refuser in primary school and on his first day at King’s had refused to get out of his parents’ car. After a year at the school he was able to make an election speech and is now in charge of putting on school productions. When I asked how this remarkable transformation had occurred, he spoke warmly about the dedication of the staff and the importance of the leadership programme.

King’s prides itself on providing an independent school education for free. They have consciously attempted to replicate what makes the best independent schools successful. As you’d expect, there’s a real focus on academic subjects and pupils are encouraged to aspire to university and professional careers. But as much emphasis is placed on building confidence and self-discipline as on achievement. In the mornings pupils follow the ‘academic arc’: maths, English, biology, chemistry, physics, languages, geography and history are compulsory to Year 11, and in the afternoons they follow a ‘creative arc’ which includes PE, the performing arts and leadership.

Of course there were aspects of the school with which I wasn’t quite so immediately enraptured. Every pupil at King’s is given (Yes given!) an iPad. This is something I’m deeply sceptical about and I’ve seen some pretty shallow examples of ‘digital learning’ in my time. But here it seems to work. Because the social norms are hard work, mutual respect and doing the right thing, no one messes about, in class or on-line. In a history lesson, pupils were asked to use their iPads to research a topic and did so sensibly and efficiently. As I’ve said before, if you get behaviour right, you can make anything work.

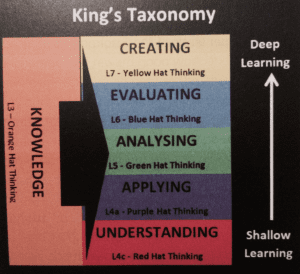

They also rely heavily on Bloom’s Taxonomy and lessons pose a hypothesis which pupils are expected to apply, analyse or evaluate.In a French lesson, pupils were asked to consider the hypothesis, ‘Learning to speak French is like building a wall.’ And what’s more they’ve shoe-horned in the Thinking Hats. But there’s a clear recognition that all of this is dependent on knowledge.

The curriculum is also interesting. Every ‘learning cycle’ takes 7 weeks and, regardless of the topic or subject studied, every teacher follows the same structure: 5 weeks teaching, 1 week of assessment and a ‘super learning’ week in which anything not mastered on the assessment is retaught.

The curriculum is also interesting. Every ‘learning cycle’ takes 7 weeks and, regardless of the topic or subject studied, every teacher follows the same structure: 5 weeks teaching, 1 week of assessment and a ‘super learning’ week in which anything not mastered on the assessment is retaught.

What I really liked about my time at King’s is that despite some of my misgivings about certain approaches to pedagogy, it was clear that everything had been carefully considered and made to fit the context. But really, none of this mattered. I might have raised an eyebrow once or twice, but my overwhelming impression was that the school is a force for good. What’s happening here in Warrington is extraordinary and on the John Gummer test, I’m certain my girls would thrive there. Sadly though, we’re a few hundred miles away and a move to Warrington isn’t really on the cards.

Are you really going to move there or were you joking?

No, I’ve moved into the catchment of a school nearby 😉

Ah right.

Friends of mine in Highgate, London, have many friends who just rent a flat temporarily in catchment area of school they want to go to, then, as soon as the kids are in the school the parents want them to be in they move back to their real house.

Isn’t that of dubious morality if not legality?

Not for me to judge. Just a very common thing, apparently. My friend disagrees with it.

Hi David

I was a co-founder of Future Leaders – cannot claim all of the credit. Many thanks for the article – we are trying to do something very different at King’s

Thanks – I’ve ammended

Thanks David, this is the second of your school reports I’ve really enjoyed, and it’s great to hear about a school with excellent behaviour through positive values not dreadful punishments.

One slightly geeky query-do many staff from the academic arc moonlight in the creative one? As a timetabler I’m wondering how they can afford to have staff teach only mornings/afternoons

I’m not sure. I do know PE staff start at 11.30

My daughter is in Year 9. She goes to the local high school about 10mins walk away. There is plenty of ‘low level disruption’ in class and many parents prefer the two other schools nearby. After Year 6 some parents from our Primary even decided to bus their children to another town.

It’s such a difficult decision! I worry about the behaviour policy where we are but a friend’s daughter achieved 9A* at our school two years ago and the school in the other town is now managed by an external team. My daughter has a great group of motivated friends, reads and talks about her reading like someone in love, is in the top sets but doesn’t want to go to University, she wants to do an apprenticeship as a chef. There are so many factors in the decision I think using one as the decider, like league tables, hardly matters. Variables come and go as do Heads (ours is leaving next summer aaagh!) and policies.

Thoughtful blogging as always. Thank you 🙂

Interesting review of school…gave a great insight. It’s a pity that much of such decision making relies on tables, reports and a short visit. We could do with a review site like Tripadvisor to help…perhaps a SchoolAdvisor 🙂

They’re given iPads because it makes financial sense for the school.

As for what makes the best independent schools successful – wealth, and the accompanying social networks it provides – difficult to replicate via a curriculum.

I worked with the UK Youth Parliament during its early days, it’s not something I’d want to see used as a model. It’s a horrible entity that encourages well intentioned youngsters to model those we mostly despise. A great shame to a childhood.

[…] Read more on The Learning Spy… […]

[…] debate. Unusually for me, I’ve mainly stood back, listened and pondered. Last year I visited Kings Leadership Academy in Warrington and although I was hugely impressed by much of what I saw, philosophically I tend […]

[…] the debate. Unusually for me, I’ve mainly stood back, listened and pondered. Last year I visited Kings Leadership Academy in Warrington and although I was hugely impressed by much of what I saw, philosophically I tend […]

[…] What sort of school I want my children to go to […]

I came here from your more recent post on ‘arguing with idiots.’ After reading this, I’m wondering if there’s a post in this blog about your beliefs on what schools are for. If so, can you direct me there?

Thanks.