Since my last foray into the world of intelligence testing, I’ve done a lot of reading about the idea that a) IQ tests are culturally biased and b) that the entire concept of intelligence is culturally biased. I want to preface my conclusions by reiterating the following points:

- I do not believe we should ever use IQ tests in schools to classify students, or to predict their academic acheivement.

- I do not believe that any group of people is in any way superior to any other group. The fact that various studies show differences in the IQ scores of men and women, different ethic groups and people of different socio-economic status has no bearing whatsoever on whether we should pursue a progressive political agenda.

- I am convinced that all differences in the average IQ scores of different groups are caused by unfair distribution of wealth, access to education and systematic discrimination. These are things that social policy should seek to address.

- IQ scores, whatever their validity, can never predict the worth of an individual. Everyone deserves to be treated fairly and with respect. The idea that we can or should select for some people’s idea of desirable traits, or engage in any other form of social engineering is reprehensible.

So, with those disclaimers made, let’s examine the argument that IQ tests are culturally biased. This argument usually rests on the finding that the average of IQ scores of different identified groups are not same. If we find that the average score of group x is higher than group y we might be tempted to say that those in group x are naturally more intelligent than those in group y, or we might conclude that the life experiences of those in group x are substantially different to those in group y ensuring an unfair advantage in the test. So, while some differences between groups may have something to do with nature, many will be due to differences in the environment. If we accept that environmental differences cause the difference in the performance of different groups, we then have two choices. We can either try to identify what these environmental factors might be – poverty, poor diet, lack of access to education etc. – and try to rectify these unfair disadvantages, or we can reject the validity of the mechanism from which we obtained the information.

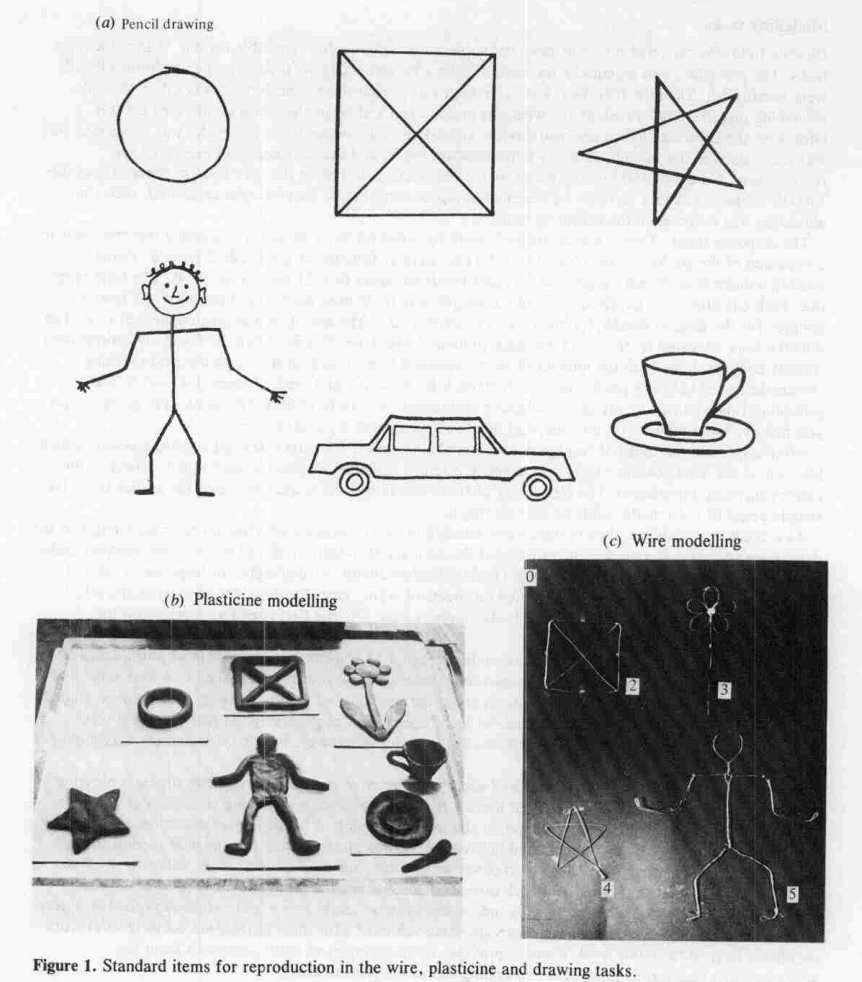

The first option is hard, the second is relatively easy. In 1979, Robert Serpell found that the media in which a task is presented makes a great deal of difference to how children from different cultural backgrounds perform. His study compared the performance of British and Zambian children and found that when they were asked to reproduce a figure using wire, the Zambian children out-performed their British counterparts, but when the children were given pen and paper, the British children did best. Serpell concluded that we develop “highly specific perceptual skills” depending on our experiences and what we have practiced. Almost all British children have extensive experience of using pen and paper to make drawings whereas Zambian children have less access to expensive pens and paper, but much more practice at manipulating found objects, such as wire, to represent the shapes of animals and people.

Serpell recommended that tests should be designed to reflect the contexts that subjects are most familiar with. He suggests that Western-educated subjects “have acquired the skills (such as drawing, interpreting pictures, assembling jig-saws and building patterns with blocks) which form an infrastructure on which the test performer must draw” and that “To measure with non-verbal pictorial tests the abilities of children whose cultural experiences does little to impart pictorial skills is just as hazardous an enterprise as testing children in a second or non-dominant language.”

Serpell recommended that tests should be designed to reflect the contexts that subjects are most familiar with. He suggests that Western-educated subjects “have acquired the skills (such as drawing, interpreting pictures, assembling jig-saws and building patterns with blocks) which form an infrastructure on which the test performer must draw” and that “To measure with non-verbal pictorial tests the abilities of children whose cultural experiences does little to impart pictorial skills is just as hazardous an enterprise as testing children in a second or non-dominant language.”

Fair points. In his masterwork, Guns, Germs and Steel, the geographer and biologist Jarred Diamond goes further. For many years Diamond lived and worked in Papua New Guinea and the book is an attempt to explain why people of Eurasian origin, and not the natives New Guinea, were the first to export the building blocks of colonialism. The question he sets out to answer is: “Why did wealth and power become distributed as they now are rather than in some other way?”

Diamond presents a typically racist explanation:

White immigrants to Australia built a literate, industrialized, politically centralized, democratic state based on metal tools and on food production, all within a century of colonizing a continent where the Aborigines had been living as tribal hunter-gatherers without metal for at least 40,000 years. Here were two successive experiments in human development, in which the environment was identical and the sole variable was the people occupying that environment. What further proof could be wanted to establish that the differences between Aboriginal Australian and European societies arose from differences between the peoples themselves?

Diamond goes on to suggest that there are two problems with the data showing differences in IQ between peoples of different geographic origins now living in the same country:

First, even our cognitive abilities as adults are heavily influenced by the social environment that we experienced during childhood, making it hard to discern any influence of preexisting genetic differences. Second, tests of cognitive ability (like IQ tests) tend to measure cultural learning and not pure innate intelligence, whatever that is.

This, as we shall go on to explore, is an empirical statement that bears some investigation.

Diamond then makes a fascinating, if anecdotal observation that New Guineans are, “on the average more intelligent, more alert, more expressive, and more interested in things and people around them than the average European or American is.” He argues that living in a ‘civilised’, urbanised environment makes it relatively easy for anyone to pass on their genetic material, as opposed to a more ‘primitive’ hunter-gather society. He argues that “…natural selection promoting genes for intelligence has probably been far more ruthless in New Guinea than in more densely populated, politically complex societies”.

Could it be that people from non-Western societies are actually cleverer and that all IQ tests are doing is providing flimsy evidence that those people with access to Western education are better at those things most valued by the Western educated elite? This is certainly a point of view with much popular appeal, but how does it stack up against the data?

For IQ tests to be unfair, getting the right answer to a question would have to depend on factors other than intelligence, such as education, social class etc. So, is this the case? In his new book The Neuroscience of Intelligence, professor of psychology, Richard J. Haier argues no, this is not the case. Part of the problem is distinguishing between fair, valid and biased. Now of course, we mustn’t get mixed up between the properties of tests and those of our inferences; a test is just a tool and it is our interpretation that gives it meaning or validity. That said, most people would be happy to say that a question is fair if the get the right answer, but is a question biased against you if you can’t answer it?

Does getting a low score on an IQ test mean you’re not intelligent? Probably. There are several possible reasons why you might not know the answer to a question. It might be you were never taught the answer, you never learned it on your own, you might have forgotten it, you might not know how to reason it out or, knowing how, you’re not able to reason it out. Haier argues that most of these reasons relate, in some way, to general intelligence.

Getting a high score, on the other hand, means you know the answers. But, does it matter how you know the answers? Have you had the advantage of a good education? Have you got a better than average memory? Are you perhaps just one of those people who are good at taking tests? Haier suggests once again that general intelligence covers all these things.

Test bias is different. For a test to be biased against a particular group, scores would have to consistently under or over predict performance of that group in the real world. By predict, obviously I’m talking about certainties; no test is ever 100% accurate in its predictions. Instead we need to talk about correlations and probability.

Haier gives the example of the SAT:

…if people in a particular group with high SAT scores consistently fail college courses, the test is overpredicting success and it is a biased test. Similarly, if people with low SAT scores consistently excel in college, the test is underpredicting success and it is biased. A test is not inherently biased just because it may show an average difference between two groups. (p.18)

But, let’s say you come across a test item you feel may be unfairly culturally biased. Thankfully, this is something IQ test designers take seriously and there’s a mechanism for raising your concerns. The mechanism is Differential Item Functioning. Basically, where the scores of people from different subgroups who got the same overall score on a test are compared to see if the suspect question is measuring in differently for different subgroups. By examining how different groups score on a question, test designers can established whether it is biased against minority groups. In this way, IQ tests strive to systematically eliminate any questions that suffer from obvious cultural bias.

Consistency is key here. If predictions are inaccurate in a few cases, that’s not bias, that’s noise. Bias shows up where predictions consistently fail to point in the right direction. Predictions not coming true aren’t evidence of bias either: if a test predicts nothing, that means it’s invalid. (Or at least, that it’s not possible to draw a valid inference from it.)

“Intelligence, whatever that is”

As I discussed here, there’s a considerable body of evidence that IQ scores have quite impressive predictive power. IQ is particularly good (although not perfect) at predicting academic success, even when we control for SES, age, sex, ethnic origins and other variables. Haier also points out that IQ also predicts various brain characteristics such as cortical thickness, or cerebral glucose metabolic rate. If intelligence tests were meaningless, they wouldn’t be able to predict anything. The fact that they can and do predict a wide range of things – including quantifiable brain characteristics – proves they have meaning.

What IQ tests don’t do, is tell us what scores mean. That is a matter of interpretation. Something real and meaningful is being measured which we have decided to call intelligence. We know IQ has implications for areas as diverse as functional literacy, job performance and being involved in road traffic accidents, but it doesn’t tell us whether these things are good or bad.

For instance, the US military won’t generally take recruits with scores below 90 because, on average, such people tend to find it harder to learn what’s required and run a greater risk of being killed in training. Is this fair? At the level of an individual, probably not. But at the level of thousands of potential recruits, that’s the decision the military has decided is in everyone’s best interest.

This is a numbers game, and while I can see it’s attractions, I’m utterly convinced that making such decisions in an education context would be entirely wrong. These are ethical considerations and, as I’ve suggested before, science makes a poor guide in determining what is right. What it does do, is give us a better picture of reality as it actually is, not as we would like it to be. This is, despite their limitations and imperfections, the value of IQ tests.

These then are my conclusions:

- Comparing people from widely varying cultures using an IQ test is probably pointless and unfair.

- IQ tests do include cultural information (general knowledge, vocabulary etc.) but great care is taken to avid this being biased against different groups.

- I haven’t been able to find any evidence that the predictions made by IQ scores are consistently wrong. If you know of any, I be grateful if you could pass the information on below.

- IQ tests clearly measure something real because they make clear predictions about performance on other metrics. It makes sense to call this thing ‘intelligence’.

- None of this tell us anything about what should be. For my money, what I believe ought to be the case is that everyone, no matter their background ought to be treated fairly. As I’ve argued here, fairness is different to equality.

- Selection by IQ is both abhorrent and unnecessary. The most useful and fair form of testing in schools is to test children on what they have been taught: what do they know and what can they do.

I agree with all six points, but with one caveat: I think schools can and should use IQ tests to identify underperforming pupils. At the Norwich comp where I taught, we used a non-verbal reasoning test with our intakes, and one year the boy with the highest score had reading and spelling scores almost at the bottom of his intake. He was also on the SEN register for behaviour. Since he came from one of our worst council estates and had glue ear, his potential would have gone totally unrecognised but for our routine tests. As it was, he got intensive help and caught up in terms of literacy before KS4–but by that time, most of his schooling was over. For my money, a good case could be made for using IQ tests around age 8. This said, I share Charles Murray’s concern that IQ has become our new caste marker, and I hope that what you’ve posted about crystallised and fluid intelligence leads to a better understanding in the profession as to how schools can help those with lower IQs to compensate for limited working memory and low fluid intelligence.

I don’t think we can say that a NVR test is the same as an IQ test. Many (most?) schools use CATs for the purposes you suggest and that is largely a good thing.

IQ tests incorporate non verbal reasoning.

Yes. And?

Ok forgive my ignorance then, but what is the difference between an NVR test and an IQ test?

Are you investigating IQ for a particular purpose David? Is it in fact to argue against schools using things like CAT?

Purpose? I’m research a book. Using CATs to help identify students who need additional help is generally a good idea.

Doesn’t this contradict your earlier claim that “I do not believe we should ever use IQ tests in schools to classify students, or to predict their academic acheivement.”? You cannot say someone needs additional help, without classifying them as someone who needs additional help.

IQ strikes me as being a lot like physical fitness: it has no moral significance, but that doesn’t mean it has no predictive power, or that there is any moral virtue in saying it has no such power.

I can easily believe that school performance tables would judge schools more fairly if they took the students IQ into account, and I don’t see how fairer judgement would be immoral.

I only ask because the longer I spend teaching the less useful I find things like CAT or IQ. In my experience all sorts of pupils with all sorts of scores have made and/or not made all sorts of progress. For the few pupils who do not despite their best efforts there is usually a significant literacy difficulty or special educational need or both. I can certainly see the significance of reading tests for example, but when I find out one person has a lower or higher IQ than another I think, “So what?! I still expect you to do your best.” Then I do my utmost to teach that person.

Perhaps it’s useful to point out that “Prediction” always means “Correlation” but not always means “Causation”. A variable “predicts” because a researcher decided to use that variable as a predictor in a statistical model. For example, IQ “predicts” academic success (and years of schooling) and academic success (and years of schooling) predicts IQ.

“IQ tests clearly measure something real because they make clear predictions about performance on other metrics. It makes sense to call this thing ‘intelligence’.”

David, tests don’t predict anything but people often make predictions based on the correlation between a predictor variable (e.g. an IQ score or SAT score) and an outcome variable (e.g. GPA at the end of first year of uni). The fact that a correlation exists of, say, 0.3 and 0.74 (a range that, according to Norman Blaikie, suggests a ‘moderate’ to ‘strong’ correlation), does not at all mean that the test ‘clearly measures something real’, let alone actually measures what you presume you are measuring. It means only that there is a correlation; any conclusions beyond that are hypothetical and require additional evidence and argumentation.

Were getting correlation Vs causation confused with correllation Vs prediction.

We can use a correlation to predict without invoking causation. In this context predict is a synonym for correllation.

I can see why you got annoyed with “clearly measured something real”, however IQ is a well established concept with an established background as a proxy for intelligence/ability.

In that sense it is as real as other concepts. Could we knock the philosophical pedantics on the head?

The causation arguments are more useful, as long as they lead us to developing interventions which reduce inequality or improve outcomes for all.

The test clearly measures something real. But mixing up correlation/prediction/causation is a common problem. This conversation is gettting bit like ‘guns don’t kill people, people do’ – with predictable disharmony. IQ is a useful tool to show whether help is needed, or whether someone is underperforming, it should not be used to predict.

The fact that IQ scores *do* predict all sorts of other outcomes is what makes them important. What I think you mean is that they can’t predict outcomes for individuals.

Does this make them important automatically? Scores in Scrabble games might also predict all sorts of other outcomes, but perhaps other tools (like tests of vocabulary or reading comprehension) might be a lot more useful when deciding what to do in an educational setting. For example, a very high IQ score can predict high achievement, but only above-level testing would tell you what children know (and what they don’t know) in each domain, allowing you to decide what to do in each domain (acceleration, differentiation…).

Therefore, it would be interesting to know the kind of educational decisions for which IQ tests are more useful (and easier to obtain) than other information. Predicting isn’t sufficient on itself. It might be in research, but not in education.

Surely you are talking about the validity, precision and appropriateness of how we predict rather then the principle itself? This tangent started because it was stated that causation can’t predict, this is demonstrably wrong.

Yes, I’m talking about the “validity for interpretation and use” in an educational context. It is indeed a tangent, but I think it’s important because this blog is about “what teachers need to know”. I’m afraid that many teachers reading this (excellent) blog could be misled by the word “prediction” (which will lead many people to assume crystal-ball-capabilities of IQ tests). What teachers “need to know” is what kind of information an IQ test can provide.

Scores in Scrabble *don’t* predict other outcomes. If they did, they would be important. IQ predicts acheivement on average but tells you nothing about what an individual knows. Nowhere have I claimed that IQ tests make useful in education. In fact, I have consistently said the opposite.

Scrabble performance might correlate with some achievement scores and therefore it might “predict” these scores. I wrote “might” predict, but a quick search for “Scrabble” and “correlation” in Google Scholar confirms that this is probably the case.

I Know that you never claimed IQ tests being useful. That’s exactly the reason why I’m trying to warn your readers for the assumptions they could make from the word PREDICT…

In response to Luc’s post below.

We shouldn’t get rid of the word predict as it’s use is valid, no should we abandon it due to the possibility of misunderstanding. Instead we could clearly state the potential misconception, avoid the unnecessary pedantry and clearly redirect the discussion.

Example: While causation is prediction it is more useful to talk about the reliability, validity and usefulness of tools in specific contexts.

My view is that, IQ’s test are not a useful predictive tool for teachers, as the information they provide is to general compared to subject specific assessments and the process of administering them is to burdensome.

You could then ask David/everyone else their opinion.

I like your posts Luc as they often clarify or change my thinking but in this case you have changed the topic/question/approach and it led to some unnecessarily meandering posts, despite the fact we agree.

David, have you researched much into the IQ of highly able art students?

No, not at all. Have you?

And then there is the issue of who should be allowed to see the results of the IQ tests. Wasn’t there a study (I’m thinking New Mexico, USA) where teachers were given fake, random, test results showing which students would progress the most, and sure enough, at the end of the year, those students had gained a higher jump in grade-level testing? (Please keep focused on testing, not ethics.)

Assuming Luc’s above level testing means context specific testing then idealy this is the useful information that would be used by teachers on a daily basis.

The expectation effect you are discribing is driven by the inappropriate uses of a general intelligence test as you are no doubt aware. I try to tell colleague’s that thinking about how staff process and use information is as useful as considering how students process information.

This frequently crops up around testing/AfL and diagnostics.

With above-level testing, I mean the administration of tests that have been standardized for “older” students. When you know that a Grade 3 student performs almost perfectly on a Grade 4 standardized test of Mathematics but not on a Grade 5 test, you have very concrete information that helps you to make a decision about what to do next. Knowing that the same student scored 138 on a IQ test won’t give you that information, although it takes a LOT more effort to administer the IQ test than to administer the test that ALL Grade 4 students in your school are taking 🙂

I was using the example to point out that “better” alternatives exist, both for low and for high scores on IQ tests, at least for some decisions.

(for more extreme variants of above-level testing, see https://tip.duke.edu/programs/7th-grade-talent-search/student-benefits/above-level-testing or https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Center_for_Talented_Youth – home of the “inventors” of above-level testing)

IQ is a useful tool to show whether help is needed.

IQ is a useful tool to predict if help is needed.

Correlation is a synonym for prediction and vice-versa. This is however separate to the underling causal mechanism’s which may or may-not be known.

Established methods of prediction can be considered real in the sense that BBC weather predicts rain. (A process that uses multiple correlations fed through predictive models). The fact it is not always accurate is irrelevant. it needs only be accurate enough to be useful.

elkysmith was being overly pedantic because if you follow those arguments to their logical conclusions you will end up with a philosophical dead-end and a lack of ability to know anything. (Think about the way we use our senses to understand the world, as well as our use of more abstract concepts).

I liked Luc’s description though I tried to reduce it down even further. Correlation = prediction but that is all.

Prediction is useful if I want to identify a struggling cohort to provide remedial teaching to.

Prediction on its own is useless for designing the intervention you are intending to provide.

From Freakonomics. US Governor finds correlation between number of books at home and poor reading and decides to give free books to all children. This achieves nothing as most books are not read, and certainly not by children. However the presence of more books at home correlates with more literate parents who are more likely to encourage children to read.

In the real world, IQ tests are (almost) never administered systematically. Most IQ tests are administered after “symptoms” occur, like systematic low achievement in one or more domains. Even before the IQ test is administered, it is already clear that help is needed, it is already “predicted” that help will be needed. Unfortunately, all too often teachers view the result of an IQ test as the ultimate “proof” that there’s something wrong with the child (and not with their instruction): “I knew this child wasn’t capable of learning, and the IQ test confirmed that”. Ironically, it is because of this kind of “brutal pessimism” that Alfred Binet constructed the first IQ test. His purpose: “We shall attempt to prove that it is without foundation” (see “Modern ideas about children”).

Therefore, the relevant question for educators should be: “will the IQ test give me more information to help this child, on top of what I already know?” How often has this been the case in practice?

The number of books is a good example. Just like achievement tests at school, it is extremely easy to observe the number of books at home. Is it sufficient to know the number of books to “predict” who needs help? Or should an IQ test first be administered to know who REALLY needs help, or what kind of help is needed? Knowing that reading a lot of books CAUSES a higher IQ score?

Bottom line: YES, prediction is useful to identify the need for help. But NO, in most cases an IQ test isn’t needed for this kind of prediction because much simpler (and systematic) instruments exist to “predict” that need.

I get your point. I had two tests via an educational psychologist and it was to confirm a diagnosis of dyslexia (I am aware of why this was a flawed approach). The detailed report was not used to alter how I was taught (and I wouldn’t expect it to be). I am also aware that as a predictive took it is burdensome and there are better alternatives with simaler accuracy which are easier to administer. I do however believe that it is used by some organisations as a predictive took (some militaries , Mensa) which it is capable of doing, not withstanding it’s inefficiencies or the possibility of more practical alternatives.

It could be helpful to clarify that “Prediction” always refers to “Correlation,” but not always to “Causation.” Because a researcher chose to include that variable as a predictor in a statistical model, that variable “predicts.” For instance, IQ both “predicts” academic achievement (and number of years spent in school) and “predicts” academic success (and number of years spent in school).