The evidence on ability grouping appears relatively well-known. The EEF Toolkit summarise the research findings thus:

Overall, setting or streaming appears to benefit higher attaining pupils and be detrimental to the learning of mid-range and lower attaining learners. On average, it does not appear to be an effective strategy for raising the attainment of disadvantaged pupils, who are more likely to be assigned to lower groups.

It appears that children who are deemed to be ‘low ability’ fall behind pupils with equivalent prior attainment at the rate of 1-2 months per year when placed in ability groups. Conversely, high attainers make, on average, an additional 1-2 months progress per year when they are set. There’s much speculation about why this might be. Here are a few popular theories:

- Low ability groups are assigned less capable teachers. Top sets are often seen as a reward, bottom sets a punishment. If low attainers are viewed as unlikely to make good progress then it might not make strategic sense to assign them your best teachers.

- When children are corralled together by ability, they learn that they are either ‘bright’ or ‘thick’ and then rise or sink to meet these expectations.

- Behaviour in ‘bottom sets’ prevents students from learning. I wrote about this here; it’s scandalous that some schools continue to allow bottom sets to be sinks of low expectations and poor behaviour.

Another more interesting idea is that setting may actually cause differences in ability. The late Graham Nuthall put it like this:

Ability appears to be the consequence in differences of what children learn from their classroom experience.

Even if not strictly true, this hypothesis is the one most likely to lead to equitable experiences for all children. There’s no doubt that some children are more intelligent than others, like most traits, intelligence distributes normally across a population. But, that doesn’t mean schools are especially good at identifying who is more or less able.

The biggest and most important individual difference between children is the quality and quantity of what they know. Let’s imagine a scenario where two students – Katie and Liam – join school mid year and need to be placed into sets. Katie has experienced successful phonics teaching and mastered decoding in Year 1, moving quickly to more interesting and sophisticated reading material. Liam on the other hand suffered with undiagnosed glue ear and was unable to properly make out the fine distinctions between different vowel and consonant sounds. Although he can decode, his ability is halting and laborious. Too much of his fragile working memory capacity is spent on sounding out letters with little left to spare for much in the way of higher level comprehension. Both pupils are assessed using a reading comprehension test; Katie scores well while Lim does poorly. As a result Katie is placed in the ‘top set’ and Liam in the ‘bottom set’. On the face of it this appears entirely reasonable, it could be the case that Liam is actually more intelligent than Katie but just knows less.

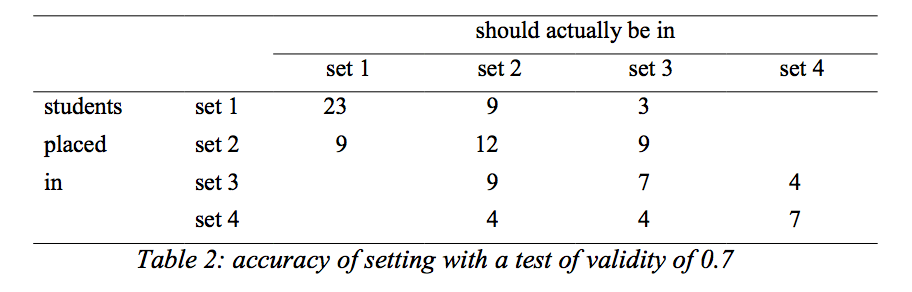

This might sound far-fetched, but Dylan Wiliam estimates that when tests are used to select children for ability groups “only half the students are placed where they ‘should’ be.” In other words, it comes down to a coin toss as to whether students are placed in the right class for their ability.

The EEF report advises schools to “recognise that a measure of current attainment, such as a test, is not the same as a measure of potential.” This is, of course, true, but more important, what happens to children’s potential once they have been set?

Let’s return to our fictitious students. In the top set, Katie is given more challenging material at a faster pace. Her early advantage is compounded. Liam though is given much more simple things to do at a slower pace ensuring that, relatively speaking, he knows less and less. The more we know, the more we can think about and the cleverer we become. Children’s experience in school determines, to a large extent, their ability. After all, no one rises to a low expectation.

Of course, none of this is fate; the research reports what has been not what could be. Conceivably, a school my have designed an approach to setting in which middle and low attainers are not held back, but we can be reasonably sure what is likely to have to children if a school’s approach to setting is broadly similar to those that have gone before.

My advice is that for the most part, we should delay grouping pupils by ability for as long as possible. If some children are holding back the progress others of others because they have not mastered basic, foundational knowledge, they should be taken out for short durations to ensure they taught what they need to know and then returned to normal lessons. Of course there are some children within the system whose needs are so acute that they need special provision; none of these comment should be seen as applying to them.

Absolutely. Even OECD senior manager Peter Adams concurs: http://au.educationhq.com/news/40003/pisa-senior-manager-says-australias-performance-concerns-justified/#

“But streaming students into high performing and lower performing streams that continue on through their schooling, and particularly that result in different career paths, access to higher education or access to skill or trade-based occupations, if that’s done too early, then that’s seen not to be helpful and it doesn’t in fact increase the overall performance of the system anyhow.

And it can be quite problematic for individual students.”

The evidence does seem quite clear here, especially in Maths (Some more here: http://www.mixedattainmentmaths.com/research–articles.html)

But still, most secondary schools in the UK set for maths. It is a big change for a teacher that has only ever taught in sets. It requires a collaborative and a supportive department. Dedicated co-planning time is essential. It needs to be well-managed, but by a group of teachers co-planning lessons for all classes (which are at the same mixed level), teachers gain confidence in their teaching and learn new approaches to teach mixed classes, which we know ultimately benefits the learners.

What different approaches do you think will be needed?

” In the US, Catholic schools do not exacerbate inequality to the same degree as secular government-funded schools, apparently because they require a more

rigorous academic program in lower-level sets and streams (Gamoran, 1992). Further research to explore this finding found two Catholic schools in which students in lower sets made as much progress as those in higher sets. This pattern was attributed to three

features: the same teachers taught both high- and low-level classes; teachers held high expectations for low-achieving students, manifested in a refusal to

relinquish or dilute the academic curriculum; and teachers made extra efforts to foster oral discourse with low-achieving students (Gamoran, 1993).”

–http://www.ces.ed.ac.uk/PDF%20Files/Brief025.pdf

May one ask: how is it envisaged that leaners will be removed to be brought up to the standard of classroom learning, when classroom learning is going on while they are away?

The class room they had no means to access due to poor literacy, you mean? I would have thought it was obvious that we need to ensure children are equipped with the basics to access the curriculum. Whatever they miss whilst interventions are ongoing would have been missed anyway.

Thanks for answering.

No, I didn’t mean literacy, so sorry for being unclear. Let’s take a particular discipline where, for whatever reason, their domain knowledge wasn’t strong. You take them out to bring this up to scratch and then reintroduce them to the on-going class. While they’ve been away, the class has moved on, so aren’t those removed always going to behind? Or am I losing the plot?

I think the ideal would be to timetable supporting interventions at specific times. There is no reason we couldn’t utilise some academic triage while focusing on core literacy and numeracy. Out of school interventions while challenging are also not out of the question.

OK – I meant literacy. Or basic maths

Totally agree…. I refer to this as ‘dragging children through’ they can’t access the learning independently so an adult sits with them and at worst does the work for them, at best spoon feeds the children through every stage.

So Liam would somehow benefit from being in a class with Katie and being exposed to material that is far above what his current level of background knowledge allows him to grasp well??? Even if he is overall more intelligent he needs the background knowledge–he can’t SKIP it. What good is exposure to advanced material that a student is not ready to grapple with? How does THAT not kill their self-concept? Liam thinks to himself, “Gee, they tell me that I am smart and capable but I’m confused and Katie here is just leaving me in the dust. They must be wrong in telling me that I can do this”.

Perhaps Liam just flat out HASN’T had the exposure but Katie developed her background knowledge over a lengthy period of time. Liam isn’t going to “catch up” by being thrown into the same class.

Depends on the accuracy of our assessment of his ability (we could have simply mis-measured)

Secondly what is the opportunity cost: Ideally we would give everyone Bloom’s one to one coaching, but if not which is more important, expectations/immersion or tailored content.

Thirdly what evidence do we have supporting our categorizations of appropriate knowledge and how reliable are their implementations.

All three mechanisms could create this scenario.

Perhaps part of the problem is that our system is looking for smooth, steady progress. Perhaps Liam will “stall” for a while while he is building his background knowledge and then, shoot ahead at some point. Other students may make excellent early progress and then hit a plateau at some point. When it comes to “individualizing” learning, we should be looking at the PACE at which students learn, the amount of repetition needed for certain individuals will vary and that’s fine but difficult to accommodate for in a full class setting. I don’t see a problem with “tracking” as long as there is the flexibility to move (both up and down) as is necessary. If students from the beginning could be in different combinations of levels in different subjects, we could better help them in what would be a “least restrictive environment” for everyone. If we weren’t so locked in to “age tracking” and “being with your peers”…

You are avoiding the point JL. If you except the argument of this post early differentiation would be the worst thing to do. Using pace doesn’t help as our expectation will of course affect that as well. In Liams case he would receive less stimulus which may slow down his progress.

It is easy to imagine a form of education overdose, but if you accept the evidence around mixed-ability teaching, logic dictates that statistically it helps more then it hinders.

I don’t agree. You fail to mention how Liam will benefit from this higher stimulus if he is lacking the background knowledge. Liam may very well end up with some big gaps in basic knowledge that will ultimately stop him from reaching his highest potential at some point if they aren’t remedied. In a large heterogeneous class it would be very difficult to figure out what he was missing and help him. Especially if he is smart enough to give the teacher the impression that he “shouldn’t” be struggling. Why is there the assumption that he’d be stuck in the “low track” forever??

I am not a huge Krashen fan but I do find much logic in his idea of comphensible input “i + 1”. Liam may be brilliant but if what you are teaching him is “i + 10” he won’t come across so bright.

JL I aid out the logic for how it could work, which is what you asked, evaluating the strength of evidence is another thing.

Liam will suffer with a lack of background knowledge. The question is will he gain from being in a more able group. While uncomfortable,negative influences may be trumped by positive factors.

We should focus on trying to get ever more good data to inform our view. Not arguing over a lack of a plausible mechanism for either outcome even if you have a preference one of them.

P.s no one assumes he would be stuck on the low track forever, we are arguing it is simply more likely that his progress would be significantly reduced over his school career due to expectations, both Liams and staff.

From the day job, the interesting thing to discuss with schools is the rationale they employ to decided whether or not to set (especially for Maths and Science). I regularly share the evidence that supports mixed ability teaching (with the possibility of a top tier set separately) up to and including Yr 10 / 11.

Often the answer to “why do you set” is:…”because we’ve always done so” and “it makes a real difference (honest guv)” – and this highlights just how difficult it can be to change perceived wisdom within an organisation, regardless of the research evidence that is out there.

For mathematics setting limits to outcomes for our young people, before we’ve actually taught them anything because each tier requires different stuff to be taught – so we set by “ability”, teach a reduced curriculum, the learners deliver a lower grade and we are justified in the setting decision we made in the first place. Hence our lower “ability” learners to less well — but their ability may well be a consequence of the set they were placed in. A circular argument.

For science, the same can be said about the use of practical work – the evidence is clear that practical work in and of itself does not lead to a better conceptual understanding of science and that increasing the practical amount actually leads to lower outcomes (as judged by GCSE and GCE grades) – this is another received wisdom area that research does not support, but to actually enact the research proves frustratingly stubborn. But I’m at risk of hijacking your post.

One of the central issues here is that (schools) we don’t spend the time needed to understand why we set, and in many cases we just continue with the previous years example. As a result we control “ability” by the curriculum we delver and produce the circular argument I mentioned above.

We have one school in our region that has recently decided to put all learners on the higher tier maths paper (yes, in the full knowledge that many learners may get a U as C is the lowest grade) – after one year, they have almost doubled their GCSE A*-C outcomes – ability appears to be the consequence not the cause.

David, as always an interesting read.

I’m going to play devil’s advocate – why not cream off the top students and teach them separately (since the evidence says that streaming helps them) and then teach everyone else mixed-ability and in line with age-related expectations? Then Kate can be stretched and Liam not overwhelmed. Or is it the presence of the brightest ones that helps to pull everyone else up?

My point is that Liam may well be brighter than Kate.

Well, that’s precisely what a comprehensive in Sawbridgeworth, Hertfordshire did when I taught there in 1968.

I think they suspect it is the last sentence.

This kind of mixed ability teaching is what they do in Finland. However, they also use very traditional teaching methods, and a knowledge-based curriculum, with textbooks guiding the curriculum. The success of this fits with what cognitive psychologists say about how progressive teaching methods tend to fail disadvantaged and/or lower ability children. It does appear to mean, however, that more able children spend a lot of class time not doing much, and professional mathematicians are concerned, for example, that not enough pupils are developing advanced maths skills at a young enough age. (The reason Finland does so well in PISA maths is because they have eliminated the tail of low achievers.)

However, when mixed ability teaching is combined with the progressive methods and lack of rigour found in so many of our schools, it seriously lets down more able pupils.

If some children are holding back the progress others of others because they have not mastered basic, foundational knowledge, they should be taken out for short durations to ensure they taught what they need to know and then returned to normal lessons.

Taken out by whom? To where? Wish we had the staff and the space to achieve this.

If schools don’t have the staff or structures to support this, they are failing their students.

We have a lot of resources we use poorly. We could try minimising diagnosis and labelling and use early interventions with those funds. We could minimise in class support and retrain them in out of class interventions and see if this improves outcomes. I don’t know the answer but we have a lot of options we could explore.

How do these short pull out sessions work? Do the students pulled out simply not do what the others did in class while they were out? Then they are essentially getting a different experience anyway. Or do they have to make up what they missed? Hardly seems fair for them to get EXTRA work.

Or are the bright students given some sort of busy work enrichment activities to do so that they don’t get too far ahead of the others? This is sadly similar to what most districts near me are now required to do with RTI (response to Intervention). The idea is to “close the gap” since that is how the schools are graded. One teacher recently stated in a staff meeting, “Oh, so we’re closing the gap by holding the top students back while we do remediation with the others”…

Arithmetic, reading, time, money, basic sentence structure, spelling,etc: Short interventions of under an hour timetabled ideally out of main class time, at home, after class, or during optional activities. Maths, English and ideally languages/humanities are off limits. Interventions are short (under 10 weeks and require ref feral not diagnosis).

Your focus on fairness is inappropriate, we know that the earlier the focus on remedial support the less damage is caused long term and the more students will be able to successfully reintegrate. RTI is promising though I would prefer more well run interventions before rolling it out nationally. Each intervention needs to be studied separately. We will need to reconsider how we spend our resources, especially staffing. If you are holding more able students back then you are seriously messing it up.

I agree that mixed ability teaching is the preferable learning environment for children. The main problem with it, in my experience, are the education experts who inevitably come in and insist you are not catering for the most able. They then tell you to create different tasks/activities for these students to engage in whilst the rest of the class do something else!

See previous arguments about differentiation and why it may not be all it is cracked up to be.

Sorry about mega paragraph. It is the only way I can get it to post.

The blog post was about setting in primary, so I think comments about setting in secondary are partly missing the point? If primary schools can be really effective in KS1 then there will be much less of a ‘tail’ when they get to secondary….so less need for setting in KS3?

Depressingly, my children’s primary uses ‘ability groups’ from Reception :- (

To be fair, I don’t think they have the resources to put in the kind of extra attention that some of the kids need…and August-born boys, for example, are mostly just not ready for formal literacy in Reception, which makes the school’s life difficult because they are expected to have them reading and writing when they should probably be doing fine motor skills, vocabulary etc…not to mention the incentives for the most effort to be invested in cramming Y6 for SATs…

My post was about setting in primary? No it wasn’t.

Katie “mastered decoding in Year 1” but Liam’s ability to decode is “halting and laborious”. Are you saying Katie and Liam are in Y7 or 8 already? If so, that’s an even more distressing indictment of Liam’s primary school than I thought. 🙁 🙁 🙁 🙁

And the answer, ideally, is still to get the early years provision right, isn’t it? By the time we get them in secondary in that state there are years’ worth of missed opportunities……

I agree with everything written here. However, I was once given a Y6 class who were all SEN and/ or recent arrivals to the country with little or no English. At first I was disgusted the school had chosen to do this- it certainly was not in the interests of these children, more about raising attainment of the others, who were being entered for SATs. But, once I was given permission to design the curriculum, tailoring it to their needs, I can honestly say, those children experienced success and a feeling of self worth. This was not something they had experienced before.

So, it’s not setting that is the problem in my mind, it’s low expectations. It is the word ‘low ability’ and the writing off of children’s potential. Add that with focusing only ‘on those children who will make the desired/expected progress’ and it is easy to see (although unforgivable) why many of our children leave primary and even secondary illiterate.

Completely agree with last post and would add to this the pernicious target grade culture. Why on earth should a child work hard, indeed at all, to achieve a target grade of 3?

Often, setting is selected as the easier option to provide for the wide variation in ability. We must ask ourselves, is it for our convenience or the pupils? Equally, where is the evidence it works in my school? Tradition should not be the deciding factor.

[…] Firstly, some teachers take the view that emojis are a fun and engaging confection with which to wrap the tedium of the subjects their employed to teach; Shakespeare is so dull and quotidian for your average teenager that only something as immediately recognisable and familiar as an emoji could possibly enable them to tackle anything more challenging. This is both patronising and demeaning. If you think young people are suckered into thinking teachers are cool just because they know what an emoji is, you’re sadly mistaken. Children might feel alarmed and intimidated by the unfamiliar but that just means that we need to bring the remoter, more abstract areas of the curriculum to life with our enthusiasm for what we teach. Children deserve better than being fed a steady white bread diet of what they already know. They thrive on the arcane minutiae we’ve picked up over long years of study; they love to hear the stories that lie beneath the curriculum and make our subjects worthy of their time and attention. Our job is not to trick kids into doing a bit of working because there’s some superficial froth that they might find distracting, they deserve for us to make them fall in love with what we have to offer. And if you want to suggest that the kids you teach just don’t get Dickens or can’t be bothered with Beowulf, just remember, ability is the consequence not the cause of what children learn. […]

[…] We also know that people’s personality and character vary enormously – some people we are drawn to, others we instinctively dislike. We know too that not everyone has the same intellectual capability. Schools divide children into ability groups and teacher these groups differently. (This, I think, is part of the problem.) […]

Hi David, interesting post. Isn’t the problem here not the fact that pupils are put into sets but that the sets are rigid?

It seems obvious to me that the best course of action is a fluid system with multiple checkpoints through the year where set movement takes place based on performance.

This clearly has large (but not insurmountable) logistic issues but carries with it many benefits – the motivation to improve into the next set up or to not drop to a set below as one of them.

This system (provided it uses fair assessment) should in time sort Liam and Kate correctly but allows Liam the space to build the basics he requires to progress to the next level. It also doesn’t “punish” Kate for her early progress by effectively limiting her exposure to challenge to ensure weaker pupils are not lost in mixed ability sets.

Hi Jim – yes, with sufficient fluidity setting wouldn’t”t present the same problems. In fact if we viewed ‘bottom sets’ as the providing the opportunity for students to catch up then all would be well. As it is, putting the children who know least in classes where they’re taught the least is insane.