…it is the peculiar and perpetual error of the human understanding to be more moved and excited by affirmatives than by negatives…

Francis Bacon, Novum Organum, Aphorism, 1620

Cargo cults grew up on some of the South Sea islands during the first half of the 20th century. Amazed islanders watched as Europeans colonised their islands, built landing strips and then unloaded precious cargo from the aeroplanes which duly landed. That looks easy enough, some canny shaman must have reasoned, if we knock up a bamboo airport then the metal birds will come and lay their cargo eggs for us too. This is the same logic as the Kevin Costner film Filed of Dreams: build it and they will come. Needless to say, despite the islanders’ best efforts, no cargo arrived. Not only had they no understanding of global trade and western science, they’d fundamentally misunderstood the causal relationship between cargo and airports.

Physicist, Richard Feynman, famously appropriated the cargo cult metaphor to describe bad science. Feynman said,

This long history of learning how not to fool ourselves — of having utter scientific integrity — is, I’m sorry to say, something that we haven’t specifically included in any particular course that I know of. We just hope you’ve caught on by osmosis. The first principle is that you must not fool yourself — and you are the easiest person to fool. So you have to be very careful about that. After you’ve not fooled yourself, it’s easy not to fool other scientists. You just have to be honest in a conventional way after that.

Trying not to fool ourselves is the key. But this is much easier said than done. Feynman points out that this kind of thinking is common in education:

There are big schools of reading methods and mathematics methods, and so forth, but if you notice, you’ll see the reading scores keep going down—or hardly going up—in spite of the fact that we continually use these same people to improve the methods. There’s a witch doctor remedy that doesn’t work. It ought to be looked into: how do they know that their method should work?… We obviously have made no progress—lots of theory, but no progress.

The Melanesian islanders had lots of theories about how to attract cargo but made very little progress. Feynman continues:

I think the educational and psychological studies I mentioned are examples of what I would like to call Cargo Cult Science. In the South Seas there is a Cargo Cult of people… They’re doing everything right. The form is perfect. It looks exactly the way it looked before. But it doesn’t work. No airplanes land. So I call these things Cargo Cult Science, because they follow all the apparent precepts and forms of scientific investigation, but they’re missing something essential, because the planes don’t land.

I’m pretty sure we get the same sort of thing going on at the chalkface. A few years ago I suggested AfL is a cargo cult with teachers perfectly replicating the form of something they don’t necessarily understand. Most cargo cults in the South Sea died out fairly quickly because no cargo arrived: it was really hard to continue fooling themselves. We don’t have this advantage in teaching because it’s so much easier to believe in the existence of cargo. After all, kids learn so what we’re doing must be working, right? All this shows is that learning is innate. We are always learning something, just not necessarily the right stuff.

We only improve in areas where we can get some sort of feedback on how well we’re doing. As teachers we quickly improve at behaviour management because the feedback is so clear: if what you do works, kids behave. If you make a mistake, they don’t. But we don’t always get better at teaching because not only go we get very poor feedback, we also fool ourselves into believing that we’re getting better because we mistake performance for learning. If we mark students’ work and in response they write an improved essay then, Hey presto: cargo! But if we’re improving short-term performance at the cost of flexibility and durability, then we might just be getting better at being worse. How would we know unless we specifically and explicitly tested ourselves and our students?

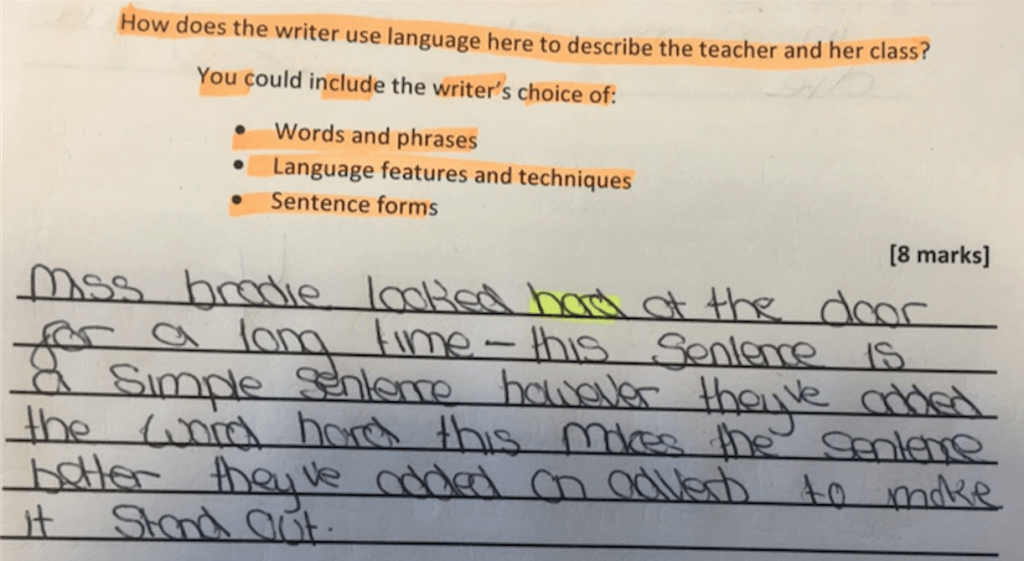

Fresh (if that’s the right word) from two days spent marking Year 10 mock exams, it’s clear that many students approach exams like cargo cultists. They know how to imitate the form and structure of a good responses but it doesn’t work. What they end up saying is meaningless gibberish:

Here’s a student who’s been taught how to build bamboo airports with no understanding of geography or technology. They’ve knocked up something that looks like academic writing but it’s empty and worthless. I suspect this sort of thing might be down to well-intentioned cargo cult teaching.

Just as it’s easier to monitor books to see if teachers are marking than it is to evaluate the quality of students’ work, it’s much easier to teach proxies and formulas than it is to teach the underlying knowledge needed to be analytical. For most teachers, the knowledge of how to write well is tacit. If it’s something you can ‘just do’, then there’s a good chance you’ve never unpicked exactly what it is that you do. There may be all sort of excellent ways to make this tacit knowledge visible to students but the only one I know which works reliably is good, old-fashioned modelling.

Good modelling requires that we share not just the content of a piece of writing but the thinking which underpins it. A few years ago I decided to take some tennis lessons to improve me game after realising I was never going to improve by watching Wimbledon every year. The coach didn’t just show me how to play, he told me how to think. We don’t learn well from watch experts perform, we need to have their performance broken down and analysed. Although I could replicate the movements required to return a serve, I had no idea what I was doing until my coach taught me to watch my opponents shoulders instead of the ball. I’m still not much good at tennis because I don’t practice enough, but I’m a lot better at watching Wimbledon because I have an idea about how a tennis player thinks.

Deconstructing exemplars can be very useful, but possibly the most effective way to share both thinking and outcome is to write a live model in front of a class and speak your thoughts aloud as you go.

Here’s an example of an exemplar written in front of a class and then annotated later as a handout:

By sharing the thinking and the outcome we can start to think about what exactly students might need to know in order to write really high-quality outcomes. Then, once students know enough, it might be useful to teach specific structures.

On this theme of modelling and explaining – Stewart Lee’s book – How I escaped a certain fate – is a great example of a comedian explaining how his act works and is well worth a Christmas read

This post is great – it seems to be a “given” among SLTs and teaching and learning gurus that all that you need to do for your pupils to be successful is give them a checklist of “success criteria”, for them to tick off. In my subject, MFL, the success criterion “give opinions and justify them,” leads to ludicrous statements such as “I like it because it’s great”. At last someone reasonably influential (you!) is questioning the concept of AFL as it has too often been implemented. As you point out, deconstructing an exemplar is far more useful. Has anyone else attempted to challenge the sacred cow of AFL?

Hey! That’s nothing: https://www.learningspy.co.uk/myths/afl-might-wrong/

Also, I wrote a book…

This post demonstrates the difference between knowledge and wisdom: I wholeheartedly concur. It seems to me that so much of what is lauded as best practice is actually window dressing. Not that you should always ignore window dressing (the “broken windows” argument , for example) but I think this post highlights the really important stuff.

Interesting distinction – not sure if I’d make it myself. I reckon wisdom is mainly the accretion of experience.

Yes the problem is, many, have over a hundred students. Teaching properly takes a long time. The learners quite often resent it and the end results can take years to accumulate. Speaking from the perspective of FE you can see how bad the teaching has got in schools. Ironically I suspect much of that poor teaching is directly related the accountability regime.

Education is a discourse. An “in conversation” that hardly relates to anything in reality. It is constructed by lots of people on good salaries who do not want to be held accountable for what they do.

We have a head of OFSTED who quotes the data his own organisation constructs to vindicate his own organisations contribution to education but does it reflect anything that resembles real learning? Independent research says otherwise.

The problem is not Cargo Cult science. The problem is that those who are clever enough to know different have mortgages to pay and and the rest just accept at face value anything that is told to them.

And yes there is a difference between knowledge and thinking well. Hmmm quite a number have spent the last few years disagreeing I have to say but anyway you are right there is far too much “teach it by number to pass exams” type leaning going on.

The consequence is not is lack of knowledge but a new type of illiteracy I call 21st century illiteracy. It’s not based upon grammar or punctuation but it’s the inability to construct coherent sentences as you so ably demonstrate above.

The evidence is clear for anyone who is looking to see. But

“A half-truth is more dangerous than a lie.

Thomas Aquinas”

Where did he write or say this?

On the internet

http://awesomeshit.ninja/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/abraham-lincoln-quote-internet-hoax-fake-450×293.jpg

Are they more dangerous than lies?

OK – I’ve taken it down and replaced it with a properly referenced Bacon quote.

Damn you Old!

[…] are likely to be taught. If we use mark schemes to work out what or how to teach, we end up with cargo cult teaching and learning. As I explained yesterday’s post, modelling is the […]

[…] are likely to be taught. If we use mark schemes to work out what or how to teach, we end up with cargo cult teaching and learning. As I explained yesterday’s post, the answer begins with […]

[…] December – Cargo cult teaching, cargo cult learning – So much of what we do in teacher follows the form and structure of ‘best […]

[…] writing, but is still only capable of producing something empty and worthless. (I call this ‘cargo cult writing‘.) Knowledge of how to write an essay is not enough – you also need to know […]

[…] do not know enough about the subject of their writing, the essays are often absurdly empty. (See here for a post on ‘cargo cult’ […]

[…] the wrong things leads to Cargo Cult Teaching. Students know what an essay is supposed to look like, they know the sorts of words and phrases […]

[…] But, as every English teacher is well aware, knowing lots of facts about, say, Romeo and Juliet, is not the same thing as being able to write an essay about the play. It therefore seems reasonable to practise writing essays. Most essay writing practice typically consists of teaching students some sort of structural device (PEE – Point Evidence Explain – or one of its many variants) and getting them to write paragraphs in which they give an opinion, provide textual evidence to support their opinion, and then either go into detail about precisely why the evidence supports their opinion, or disappear down some rabbit hole exploring the subtleties of the quotation. On the face of it this seems to work because some students seem to get better at writing such paragraphs, but for every student who seems to gain increasing confidence there always seems to be another who slavishly follows the structure without saying anything of any interest or originality. I’ve come to think of this as cargo cult writing. […]

[…] understood principles. We lose the ability to make considered professional judgments and embark on Cargo Cult teaching – following the forms and structures of teaching but without understanding the underpinning […]

[…] are not skills because they do not improve through practise. Practising essaying writing leads to cargo cult essays. Practising inference is a dead-end that not only wastes children’s time but sucks all the […]

[…] As with most subjects, the step up from GCSE to A level English literature is tough. You can get a pretty good grade at GCSE without developing a critical style or understanding much about the art of constructing an academic essay. Students’ work is routinely littered with stock phrases such as “I know this because” and “this shows” all of which shift the focus from having to think about subject content in sophisticated ways to simply learning a collection of fail-safe formulas. At its worst, this becomes cargo cult writing. […]

[…] their craft. They are prey to the lethal mutation, and the dangers of cargo-cult teaching (see here for David Didau’s excellent post on this). The encouraging nodders may never really improve […]