Every weekday morning, my daughters both moan about having to get up for school. They moan about their teachers and they moan about homework. Given free rein, they would spend all day every day watching BuzzFeed video channels, making Spotify playlists, watching Netflix and taking online quizzes. It’s not that they’re lazy, it’s just that they’d really rather not have to learn maths, science and geography.

They’re both moderately conscientious, reasonably hardworking girls who never put a foot wrong in school. On parents’ evenings, we’re regaled with tales of how good their attitude to school is and how much progress they’re making. Broadly speaking, we’re pretty happy with this. We send them to school knowing that, for at least part of each day, they’re going to be bored, frustrated and uninspired. We know they don’t like some of their teachers and don’t see the point in some of the subjects they’re expected to learn. And knowing all this we are fully supportive of their school.

Why? Because it’s not the job of a teacher to do what students want. It’s not the job of a teacher to entertain children or present them with endless ‘engaging’ activities. The job of a teacher is to teach the curriculum and support students in their understanding of it.

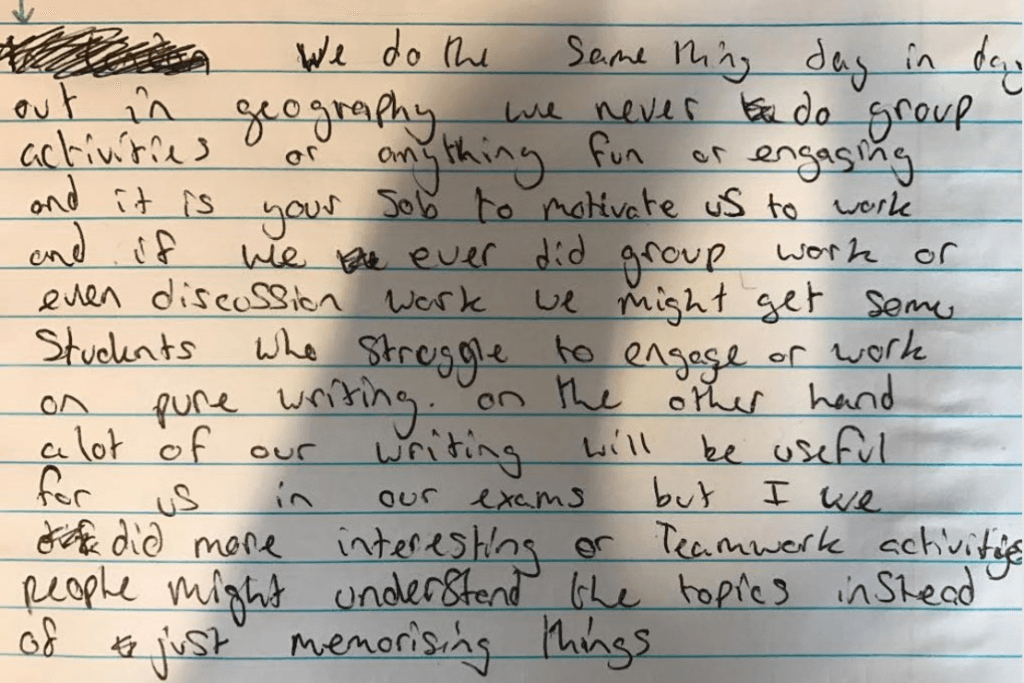

I say all this because a teacher on Twitter has been circulating a note his or her son wrote to his teacher:

Here’s a transcript in case you’re put off by the handwriting:

Here’s a transcript in case you’re put off by the handwriting:

We do the same thing day in day out in geography we never do group activities or anything fun or engaging and it is your job to motivate us to work and if we ever did group work or even discussion work we might get some students who struggle to engage or work on pure writing. on the other hand a lot of our writing will be useful for us in our exams but I we did more interesting or Teamwork activities people might understand the topics instead of just memorising things.

Now clearly I can’t comment on this young man’s geography lessons, maybe he’s entirely justified in feeling this way, but to present this, as their parent did, as a reasoned argument against whole class instruction is a pretty poor show.

The first thing to point out is that this student has clearly not memorised guidance on sentence structure. They may or may not understand how a written sentence needs to be punctuated for clarity, but this understanding is not something that they are able to effortlessly retrieve from long-term memory. My purpose here is not to belittle a child, but to show how they have been let down by their experience of education. This sort of basic grammatical understanding is simple enough to be fully automatised. It’s not enough for students to understand how grammar is supposed to work, they have to be able to use this understanding without having to think. The purpose of “memorising things” is to free up mental space to be able to think about more interesting things without giving people who don’t know you grounds to discount your opinion as uneducated.

Now to the substance. While the letter writer acknowledges that a lot of the writing completed in class will help his classmates to perform better in their upcoming exams, they’re unhappy that these activities are the same “day in day out”. I have some sympathy with this. One of the greatest blights on secondary education in England is that a disproportionate quantity of time is spent preparing for exams. The received wisdom is that by getting students to complete written tasks which correspond to the sorts of things they’ll have to do in exams, exam results will go up. I’m not at all sure that this is true. Daisy Christodoulou makes a good case, in Making Good Progress?, for formative assessment only to apply to formative tasks instead of, as is currently the case, endlessly trying to formatively assess summative tasks. In this case, the student’s experience of geography might be improved if more lesson time was spent on learning the detail of different geographical concepts and how they apply to a broader range of contexts. In addition, instead of repetitively practising essay questions, it might be beneficial to master some basic grammatical skills through decontextualised drill. Hang on though, wouldn’t decontextualised drill be even more boring? Well, that’s entirely up to individual teachers. Such purposeful practice can be made more inherently interesting through competition and interactive instruction.

This takes us to the main source of this student’s gripes: they want more groupwork. This is interesting. Even at the height of my full on prog phase of teaching I found that students had a pretty mixed opinion of groupwork. Generally speaking, hardworking, quiet, conscientious students hated it, whilst most others only really appreciated the extra opportunities afforded to chat with friends. Only the most extrovert really seemed to look forward to it. My teaching became an exercise in devising cunning techniques to keep students on task, either by designing tasks in such a way as to minimise opportunities for off-task chatting or by conceding to the unquenchable thirst for fun. Both my own children have negative views of group work. My youngest daughter hates it. She’s inevitably split up from other sensible, hardworking students and make to work in a group with more feckless characters. She often ends up doing all or most of the work in order to avoid her teachers’ opprobrium. My eldest daughter is more charitable; she really enjoys group work in drama and is forgiving of some of the tricky characters she’s expected to supervise. Her preference is for paired work during which she can chat away with another like-minded student. There needs to be a much better justification for group work than that a few children like it.

As time’s gone on I’ve become increasingly disenchanted with the motivational powers of fun. Obviously I have nothing against children enjoying lessons, but to make fun the object is, I think, a betrayal of what they really need. I argued here that children having fun is a poor reason for selecting an activity, and here I suggested that some forms of ‘engagement’ may actually do more harm than good. There’s good reason to think that the causal connection between motivation and improved performance might not work the way most people seem to think; it appears more probable that improved performance causes students to be more motivated rather than the other way around. To that extent, if it is a teacher’s job to motivate children then probably the best way of achieving this aim is to ensure they have mastered the subjects being taught.

To sum up:

- Teachers are not responsible for entertaining children or making them happy. And they certainly should not be responsible for children’s mental health. Ideally your passion for what you teach should be infectious, but this is not the purpose of teaching.

- Different children like different things. There’s no way you can please them all so your best bet is to concentrate on teaching students to master what you’re employed to teach.

- Teachers should not feel ashamed of doing the same thing “day in day out” as long as what’s being done is more than just exam prep.

- Motivation is most likely to stem from success and students are mostly to be successful when taught via interactive whole class instruction.

- Kindness is important but it’s worse than useless without being both fair and firm. Never feel you have to apologise for making students work hard.

A little autonomy might do the trick.

“Allowing individuals to exercise control over the environment may not only satisfy a basic psychological need (Deci & Ryan, 2000; 2008; White, 1959) but may be a biological necessity (Leotti & Delgado, 2011; Leotti, Iyengar, Ochsner, 2010). Studies with both humans (Tiger, Hanley, & Hernandez, 2006) and other animals (Catania, 1975; Catania & Sagvolden, 1980; Voss & Homzie, 1970) have shown that both prefer an option leading to a choice than an option that does not, even if this option results in greater effort or work— suggesting the existence of an inherent reward with the exercise of control (Karsh & Eitam, 2015; Leotti & Delgado, 2011). Along the same lines, Eitam, Kennedy, and Higgins (2013) demonstrated that human motivation is dependent on (the perception of) one’s actions having effects on the environment. Even if the effects of one’s actions are trivial, intrinsic motivation is enhanced if the performer has control over those effects (termed Control Effect Motivation by Eitam et al.). Conditions that provide an opportunity for choice may be motivating, because they indicate that one will be able to control upcoming events.

(…)

Importantly, even giving individuals choices that are incidental to the motor task has been demonstrated to have a positive effect on the learning of that task (Lewthwaite, Chiviacowsky, &

Wulf, 2015). In one experiment, allowing participants to choose the color of golf balls they were putting led to more effective task learning than a yoked condition. Giving participants a choice of ball color also has been found to increase the learning of a throwing task (Wulf, Chiviacowsky, & Cardozo, 2014). In a second experiment by Lewthwaite et al., the findings were even more compelling: The learning of a balance task (stabilometer) was enhanced in a group in which participants were given a choice related to one of two tasks they would practice afterwards and in which they were asked their opinion as to which of two prints of paintings should be hung in the laboratory. That is, relative to a yoked group that was simply informed of the second task or the print to be hung, the choice group demonstrated more effective retention performance on the balance task.”

http://bit.ly/2quHk0o

I have had many conversations regarding this topic over the years. I really enjoyed reading the post. I would love to know what the teacher’s response was when presented with the note!

I can’t help you with that, sorry

Without knowing any details, or background or anything at all you have made sweeping assumptions in the most judgemental way.

You choose to ignore a child’s wish for deeper learning and understanding. His recognition that some in the class are struggling and, his expression for a different way to learn some of the time.

Have some respect for children who wish to learn and may struggle with a diet of drill and recall only.

I haven’t made any judgements or assumptions. Children’s wishes are a can of worms. Education academics don’t agree on what ‘deeper learning’ is so taking a child’s opinion, no matter how heart felt is unlikely to be of much help. Children have very limited capacity for diagnosing why their peers are struggling and even less insight in to how they can be supported. In this instance, group work is the very last thing a struggling student is likely to need.

Have some respect for teachers who are doing their best in an unforgiving climate to educate our children. Parents publicly sharing their children’s complaints is unpalatable to say the least.

Come on. That’s emotional blackmail and there is no point saying that others have made sweeping assumptions and replacing them with your own. More importantly the post is not really about the letter directly but how it is being used in a debate on teaching methods.

You could just flip your last sentence to

Have some respect for students who wish to learn and struggle to get much out of group work and inquiry learning.

This would be equally unhelpful. There are more reasonable ways of challenging the ideas here.

Presumably you sought permission from the child’s parents to use their letter to further your own career?

What the parent who posted the letter on Twitter? That’s a very uncharitable interpretation of my motivations. Makes me curious about why someone who has blocked me on Twitter is now posting on my blog. Is this an attempt to further your career Debra? Presumably you’ll have a whip round to begin legal proceedings?

Nice response.

I just can’t understand. Teaching is so draining and challenging enough with so much criticism from so many fronts. No one wants to teach and the ones still placing their heads above the parapet get shots in their backs. No wait ….are either of you still at the front? Eh, sorry.

Cheap shot.

“it is your job to motivate us to work” NO, IT ISN’T.

If one of my children were ever to say that to any of their teachers they would get a long lecture from each of their parents and would be made to apologise to that teacher.

Had a discussion with Y10 today, told them 100 years ago they’d have been in the mill or down the mine and they should be grateful for their free education.

Ideally, of course, the geography teacher would have sufficient time, energy, patience, resources, proper curriculum planning to work from, charm and joie de vivre to give the class a really fascinating and effective lesson. Most of those things have almost disappeared where I work….

Good for you!

Why have you used a piece of child’s writing, without permission? Please consider deleting this.

Disengenous. It was originally shared by others to make an argument in favour of a style of teaching.

1. The child’s mother chose to tweet a picture of a letter her child wrote to make an ideological point.

2. Twitter’s terms of use make it clear that by tweeting you give up all rights to being asked permission

3. Why are you, a progressive troll, reading and commenting on my blog?

‘My purpose here is not to belittle a child, but to show how they have been let down by their experience of education.’

You made some good points but could have written exactly the same post while avoiding harsh and personal criticism. If you need to clarify a comment as not ‘intended to belittle him’ then you must know there is a danger of it coming across that way. Are you sure this child even wanted his mother to post the comment? Even if he did you must know that he’s unlikely to want a public grammar lesson.

If you’re not belittling the child then you’re belittling his school for not yet teaching him perfect grammar. I don’t even know how old this child is, or his educational background. I feel that the post would have worked perfectly well with general points and no personal remarks that the child involved might read.

I am not a teacher and I respect people on both sides of the trad/prog debate. I do agree with most of your points, but mostly I feel sad to see a post that so carelessly risks hurt to a child.

I don’t think this post considered the young person who wrote the letter.

Belittling and criticising are not the same things. I am critical of an education system which turns out young people unable to write grammatically. That seems an entirely reasonable position. I’m also critical of this young chap berating his teacher for not teaching the kind of lessons his mother has told him would be preferable.

As to carelessly risking hurt to a child, the only reason he’d read this is if his mother showed it to him. I’d also make the point that as his mother chose to tweet his letter to make an ideological point, it seems fair game to rebut that point.

I don’t always like David’s arguments when he is annoyed but the points you made are unreasonable. The child will not be the one reading this and it is hardly harsh. The insult here is perceived and would be so no matter the words used. Witness responses to Greg Ashman’s blog posts. Reread the style and nature of the arguments made on both sides (on different blogs-ignore the content at the moment focus in the style). You will see this kind of outrage is normal irrespective of how ideas are presented.

Sorry David. On my phone and didn’t realise you had responded already.

At a previous school, “flex” time was offered, wherein students could choose how they wanted to spend an hour each day. Options included everything from math support to learning how to do hairstyles to going for a walk – or skipping the hour altogether (though the latter was not actually an option, just an unintended consequence). This was a waste of time where students rarely made appropriate educational choices and were, in fact, robbed of one hour of structured lesson time. I would discuss this with students, who readily admitted it was a joke.

The school was obsessed with “student choice, student voice.” When teachers like me complained about the system, citing research and statistics pertaining to the program at the school (eg. 20% regular absence rate from flex time), it was decided a student survey would be implemented. Students voted to keep flex time.

I asked a number of students why they thought it turned out this way, and whether they wanted to share their survey comments. Quite a few had voted to keep flex time, despite the fact that they were receiving less instructional time in structured classes than the curriculum was designed for. They said they’d rather have “free time” for fun things, or to skip altogether and hang out with their friends. Trying to explain the disadvantage of losing instructional time in the timetable was met with intellectual understanding, which was overturned by an emotional impulse to personal gratification.

[…] on lessons always being exciting and fun from a students’ perspective, as David Didau argues in a recent post on education website Learning Spy, is potentially misguided. The conventional wisdom is that if […]

Respectfully – please take down the transcript of my son’s note. You do not have permission to use it. You have not sought to find out any details, needs or context before making your comments. What is on social media is not yours to do with what you want. See link

http://www.bbc.co.uk/webwise/0/22718822

The link was not helpful as it is talking about defamation. Someone disagreeing with you is not sufficient grounds. You have asked him to take it down that is reasonable.

Can I inquire if you will be continuing to use the note on social media as evidence of flawed teaching?

Also is David correct that you are a teacher and did you share the letter about another practiconer?

Practitioner.

Sorry Kate, I’ve removed the image out of good will but the transcript stays. I don’t need or want any further context beyond the fact that you used it to make an ideological point on a Twitter. Please feel free to write a rebuttal of my points rather than engaging in petty minded, legalistic attempts to shut down debate.

Hi Dave. Usually I think you strike some chords, but this time your blog is tendentious and flawed in a number of ways. Who are you helping with this blog? Teachers? Parents? Pupils? I don’t think so. Let me explain.

Firstly, denouncing the kid this way for his writing does not really support the main argument of your blog, so I’d regard it as a fallacy of argument. A red herring, I think – though the observation in itself may be correct, it’s not truly in line with your reasoning, is it? Plus, you’re attacking the pupil on his not-yet-perfect writing / interpunction. That’s an Ad Hominem – and you probably know it. Which means you’re actually cheating.

Secondly, you offer yourself and your children as “experience experts”, as we call it in The Netherlands. Technically, that’s another argument fallacy – a hasty generalization. It may be that you and your kids do or do not like group work, but a. it really does not matter nor aid the discussion b. the subject of your blog was not assessing the use or fun of group work. Messy.

Thirdly, more importantly, educators may actually develop themselves and become better, more efficient teachers, if they took their pupils’ feedback to heart. Research shows people learn lots from doing a task, then getting feedback on it, then correcting errors. This goes for students as well as for their teachers.

If I’d received this kid’s note, I would have thanked him for his feedback and would’ve worked on making my lessons more effective in getting my students to attain mastery. I want my pupils to learn from my feedback – and I can learn from theirs, if it’s accurate. This way, giving / receiving / gathering / asking for feedback becomes increasingly normal. Thus, kids learn to ask for feedback to propel their own learning.

Of course I know what you were on about: teaching should not have to be “fun”, that’s not the point – it should be about getting kids to learn as much as possible. Yet, the thing is: kids do learn less from boring lessons. They’re not challenged or pushed enough to face difficult tasks and improve their performance. That’s not their own mistake, as the kid pointed out quite correctly. That’s their teachers’ job.

Which is why I see no use in you “defending” monotonous teaching here. Boring teachers are less effective on the job than the ones who can get their pupils to work hard and learn a lot of new things. Teachers should be inspiring – they should get kids to do what it takes to learn (and be satisfied after). You know that as well as I do. So who are you helping here?

Sergej you have clearly laid out argument but it strikes me as having serious flaws in its’s form.

Tendentious “expressing or intending to promote a particular cause or point of view, especially a controversial”. In this sense the word can be freely applied to both sides.

Criticism of the child’s writing is not an ad-hominen as it is being used to demonstrate the need to practice skills which are unpleasant and frequently un-enjoyable.

You may find the use of this argument inelegant and distracting but it is a poor example of this fallacy.

The entire debate is centred on the use of a letter by a child advocating a type of teaching. David simply used his children to demonstrate that they have a different point of view.

The article clearly references group work which is also frequently used as part of the other approaches it mentions.

You are correct about feedback but the quality matters. Hattie mentions that a lot of feedback has negative effects. though in general however the positive effects outweigh the negative. For this feedback to be effective it needs to be accurate and reasonable. We have to little information here to judge that. The letter should also have not been shared if this was the primary intention and even then it could easily be considered rude, especially if it is true the parent is also a teacher.

You describe how you would have reacted but this is only reasonable if you assume the feedback is valid and that the proposed changes would improve learning. Many would not agree with that premise. Finally no one believes in boring lessons only in different priorities and compromises and there are serious disagreements on the best way to get people to learn

It is my hope I have clearly demonstrated how your underling assumptions have effected your conclusion’s. I appreciated how clearly you laid out your points and have attempted to reciprocate in kind.

The pupil makes a point that is to a degree in line with current research. Interactive work does enhance learning http://chilab.asu.edu/papers/ChiWylie2014ICAP.pdf. Whether it’s a teacher being more interactive with pupils or pupils having opportunity to be constructive-interactive amongst each other. Which is quite well possible with well-structured cooperative tasks, but also depends on the classroom climate/working atmosphere established already. And generally speaking, structured cooperation in various mixed groups (teacher-chosen) diminishes social distance in the group, which is beneficial for working atmosphere.

For the rest, I really agree with Sergej. But I’m also from the Netherlands.

Of course it works. As Hattie said everything works. Direct comparisons however tend to show explicit works better. You have just done the classic cherry pick. David talks frequently about opportunity cost which is important here?

The sharing of a letter critising another teacher’s approach knowing full well the fault line in the proffession is suspect. Finally the child obviously has the same view as their parent which makes a from the mouths of babes argument suspect.

Personally I would have preferred this entire argument not to have existed but the hypocrisy is irritating.

A couple of thoughts from the Scandinavian outback…

A discussion for and against group work ought to lead to the conclusion: It depends on two(at least) things.

It depends which quality of knowledge of knowledge you want to achieve.

Group work is more suitable for understanding and adaptation BUT whether that is possible or not depends on the group having sufficient pedagogical maturity to handle a more autonomous pedagogical method. If it doesn’t the result is “chaos”.

It also depends on the group having sufficient basic knowledge to use as building blocks in the creation of understanding. If they don’t the result again is” chaos” and group work is not the most efficient way to teach basics.

Talking about motivation I have often heard it being said that the foundation for motivation is fun and enjoyment, maybe after observing visibly motivated and enthusiastic people. But many times in life you are faced with making choices where neither option is fun. Where do you find the motivation to endure the consequences of your choice? By UNDERSTANDING the point. If I don’t understand the point of learning grammar I will be hard put to find any motivation. Some may find their point in keeping the teacher happy, getting good grades but that will not make it more fun. Just help with the motivation.

Some observations

“Group work is more suitable for understanding and adaptation” – This needs to be proven.

A earlier post of Davids talks about motivation on the PIDSA tests. The results were contrary to you expectations, students enjoyed learning when they had obtained some mastery.

It is hard to understand the immediate point of most challenging content. The act of mastering it gives you knowledge of its use.

[…] less sanguine, however, when parents use their children as their political spokesperson. From the sharing of their child’s notes written in class, in which they obviously parrot what they have heard at home, to the young child […]

Hi there, I’m just about to start my NQT year next year and I’ve just completed my research essay as part of my PGCE.

I hope that you can see this is something I’m truly passionate about and have thoroughly investigated. I’m anot avid reader of fantasy, philosophy, sociocultural studies ando cognitive behaviour.

I invested my time researching in to the ideologies behind PHSE. It comes of a place looking for holistic education. That is one that tends to our emotional well being. According to the philosopher Hegel, and also apparently in many other texts, we need three things to be happy. The first of which is solidarity with one own community, this is comes across as the need for group work, but for this to work, they need to be given roles and feel like they have a place within the mini society that is a classroom.

Second is knowledge of truth, they want to learn but they want you to be honest with them. We all have an intrinsic want to learn, when we push them to study for a test we forget to find out what they’re potential is. We need to be sure of what we do in a classroom is for the good of everyone involved.

Lastly we have the need for radical freedom. We need to learn to be autonomous, we learn this by being part of the community, and taking care of our responsibilities. So trust your students more, give them roles, but make sure they’re ones they want to except, any you make them do will just come of as an exertion of power. Lastly, it will take time for this to work, they have not been trained like this so far and many not taught to think for themselves beyond when told to hold a 2 minute conversation with their partner.

We may not have had this as an education but does that mean they don’t deserve a better one? The only thing I’m really saying is to be a human, be compassionate. Stand up for the wrongs that actually have a detrimental impact for someone, but be understanding in those that don’t and always understand that behaviours are learnt, and so can be unlearnt.

Kind regards,

Jennifer

[…] Should teachers do want children want? – 19th […]

[…] We know that looking after the interests of our students lies not in making them happy and doing what they want, but in doing what’s best for them. Students are not yet adults, and as such, they’re […]

[…] Should teachers do what children want? – David Didau […]

[…] Students need to learn, not be entertained […]