While people are entitled to their illusions, they are not entitled to a limitless enjoyment of them and they are not entitled to impose them upon others.

Christopher Hitchens

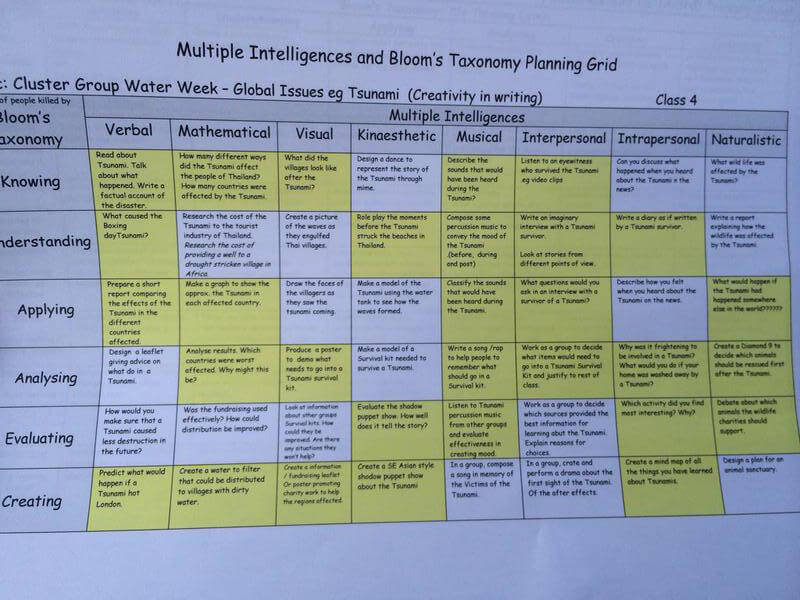

Twitter exploded into fury earlier this evening when @MissNQT posted a picture of a training resource she’d been given at a course aimed at helping newly qualified teachers to challenge more able students.

I took it upon myself to further propel it into the Twittersphere with this:

Hyperbole? Schools Week editor, Laura McInerney certainly thought so. She suggested that were the grid retitled nobody would have gotten aeriated. Here’s her edited version:

Is she right? I’m still not happy with it. Laura claimed that many of these activities might actually be challenging, and was also a handy way for busy teachers to devise extension activities on the fly.

To an extent, she has a point; we’ll come to her arguments later. But my point is that the titles hadn’t been changed. Newly qualified teachers are probably more vulnerable to bollocks than anyone else and surely it behooves us as a profession to ensure that anyone tasked with training them how to be better teachers has a responsibility not to perpetuate a belief in highly dubious theories of knowledge and intelligence. It’s not that I think any individual has behaved shamefully, more that it’s shameful our profession is so endemically deluded. I don’t really mind if any individual teacher thinks this is a good idea and wants to use it, what I object to is that it’s foisted on others as a good idea with spurious claims to authoritative evidence.

To be clear, Bloom’s Taxonomy is not so much wrong as epistemologically unsound. The standard assumption is that ‘knowing’ is a necessary, but pedestrian platform which supports all the sexier ways of manipulating information with ‘creating’ perched at the apex of a pyramid of skills. This is an article of faith to many teachers and one I challenge in my book:

Sometimes it’s harder to remember than it is to create; recalling how an engine is constructed is far more challenging than designing an experiment to test the temperature at which water boils. Equally, it may be more difficult to understand than evaluate. In fact, fully understanding a concept makes evaluation of it fairly straightforward. Just watch how quickly and precisely an expert baker like Mary Berry evaluates the shortcomings of a poorly baked cake, or an expert choreographer like Craig Revel-Horwood picks apart a badly executed tango; they can do this because they have complete understanding – that is epistemic knowledge of the ‘underlying game’. (p150)

Re-labeling these things ‘skills’ is even less useful. ‘Knowing’ isn’t really a skill (although we can improve our ability to retrieve information) it’s the accretion of stuff in long-term memory. And we get into difficulties if we decide ‘Understanding’ is somehow qualitatively different to knowing. If you don’t understand something then you don’t really know it, and is it actually possible to understand something you don’t know? The rest of these ‘higher order’ skills depend entirely on domain specific knowledge. Evaluating in English is different to evaluating in history, science, dance and technology. Evaluation in maths probably uses the word most accurately; it essentially means ‘solve’, or ‘find the value of’. You really can’t see these skills as distinct from subjects.

I’ve got more to say on the subject of taxonomies in the book, but let’s move on to Multiple Intelligences. I was dismayed to hear Sir Anthony Seldon parroting this theory off as factual in a debate on the nature of intelligence at the Education festival last week. This is simply unacceptable.

In Intelligence: All That Matters, Stuart Ritchie says this:

There’s just one problem with this theory: there’s no evidence for it. Gardener just came up with the concept and added the additional intelligences seemingly on a whim. At no point did he gather any data, or design any tests, to support his idea. The notion of ‘multiple intelligences’ has become very popular among educators as a kind of wishful thinking: if a child poor (say) logical-mathematical abilities, the argument goes, they might still be good at another kind of intelligence! But denying the huge amount of evidence for general intelligence does nobody any favours. (p27)

In his brilliant contribution to my book, Andrew Sabisky also wades in to provide a brisk but comprehensive takedown of MI. As he says, There are two main criticisms to be made of [Howard] Gardener’s work: the first that it is conceptually confused and the second that it is empirically false.” (p391)

It’s just not good enough to go around perpetuating these faulty ways of thinking and presenting them as incontestable fact. Ignorance really is no defense when it comes to training teachers. We have a professional responsibility not to sharing guff. Research literacy- the ability to work out when we can trust the ‘experts’ – liberates teachers from the burden of bad ideas.

But back to Laura’s points. If the worksheet had been presented without these unhelpful labels and merely as suggestions for providing challenge within different subject domains, what that have been acceptable? Well, in a way perhaps. Although there are plenty of duds, there’s enough on the list which might provide students with some challenging learning opportunities. If as she’s suggesting, it’s merely a menu of potential extra-curricular activities with which to engage young people, then fine.

But it isn’t: the suggested activities are explicitly presented as ideas for geography lessons on tsunamis with the stated aim of getting students to write creatively. Writing creatively requires far more than doing a spot of role-play (Understanding/Kinaesthetic), thinking up interview questions to ask a survivor (Applying/Interpersonal), or making a tsunami mindmap (Creating/Intrapersonal). If we want to develop students to write in geography then they need to know the conventions of geographical writing. If we want them to write a poem or perform a dance, these are both entirely valid means of expressing thought but not particularly useful to your average geographer. This presents teachers with a choice: you can either spend time teaching children how to write poems with the consequence that you have less time to teach them about tsunamis, or you can leave their writing of poems (or any other non-geographical form of writing) to chance and accept that many students’ work will not only be a waste of an opportunity to teach them to write geographically but will also undermine their ability to write well because due care and attention will not have been given to the process of writing. Writing well requires careful modelling, scaffolding and practice. Lose lose.

So what of the argument that this type of thing, if retitled and repurposed, might make a handy resource for busy teachers? The internet abounds with this sort of thing and I can see the appeal. The tyranny of engagement forces us to scratch about for novelty, no matter its worth. I’ve written about some of my issues with this way of thinking here, here and here. But in summary, my main objection that what is engaging is often distracting and cause us to remember the activity but forget the purpose behind the activity. The act of colouring in a poster on what to put in a tsunami survival kit (Analysing/Visual) may be more memorable than all the details you were supposed to be learning about tsunamis.

In her final challenge to me, Laura said she looked forward to hearing about how I would go about challenging and extending students. In my book, I describe an uncontrolled study in which I had the task of increasing the aspirations of a group of highly able but demotivated Year 10 students:

We explained to the pupils that we were going to give them a series of challenges designed to get them to make mistakes so that we could give them meaningful feedback on how to improve their performance.

Firstly, we tried getting them to complete tasks in limited time: if we deemed that a task should take 30 minutes to complete, we gave them 20 minutes to finish it. The thinking was that one condition for mastery is that tasks can be completed more automatically. Also, by rushing they would be more likely to make mistakes. This had some success.

Next, we gave the pupils tasks in which they had to meet certain demanding conditions and criteria for success. These were difficult to set up and always felt somewhat arbitrary in nature. For instance, in a writing task, we made it a condition that pupils could not use any word that contained the letter e. This kind of constraint led to some very interesting responses but, ultimately, the feedback we were able to give felt superficial and was deemed unlikely to result in improvement once the conditions were removed.

Finally, we decided that we would try marking work using A level rubrics. This had a galvanising effect. Suddenly, pupils who were used to receiving A* grades as a matter of routine were getting Bs and Cs. The feedback we were able to give was of immediate benefit and had a lasting impact. When interviewed subsequently, one pupil said, “For the first time I can remember, [the teacher’s] marking was useful – I had a clear idea of how I could get better.” (p 264)

Tasks should be sufficiently challenging that every student will struggle. Those who struggle more will require more scaffolding for longer. If students finish early, then maybe the task wasn’t open-ended enough? Maybe it needs to be proofread? Maybe more practice is required? Either way doing a puppet show should really be an option.

This might sound as much fun as designing a plan for an aminal sanctuary (Creating/Naturalistic) but it’s far more likely to result in students mastering tricky concepts and acquiring challenging skills. Or, at least, that’s what I think.

As Nick Wells pointed out, it’s exactly this kind of thinking which resulted in one of the worst indie songs of the 90s:

Please feel free to politely disagree below.

I read, and participated, in the twitter discussion, My feeling was that Laura’s argument was missing the point, and I think you’ve captured that here. I don’t have any issues with someone evaluating a puppet show about the Tsunami, for example. I have an issue with that being an way to ‘demonstrate’ Kinaesthetic Evaluation, or that Kinaesthetic Evaluation even has a meaning. If ten people evaluated a puppet show there would probably be ten different foci – the acting, the quality of the puppets, the story, the emotional result, the puppetry etc etc. It’s offensive to NQTs an teachers as a whole that activities are pigeon-holed in this way.

“I see you asked the class to evaluate the puppet show. What did you do for the visual learners?”

“They saw the puppet show as well, didn’t they?”

What horrifies me the most is the continued existence of VAK anywhere near teaching.

The problem is that Bloom’s Taxonomy is so ingrained in ed research circles, that it’s going to take a minor miracle to purge it. Just do a search in Eric and get ready to be depressed. For example, her’s a study from 2013…just look at the assumptions!

“Bloom’s taxonomy has been widely used across many disciplines to align course objective and curriculum to level of skills achieved (Dettmer, 2006; Green, 2010; Irish, 1999; Manton, Turner, & English 2004; Su et al., 2005). One frequent observation is that many college courses emphasize rote memorization of factual content or factual minutiae, even though students tend to show poor retention of this type of information (Lord & Baviskar, 2007; Zheng, Lawhorn, Lumley, & Freeman, 2008). Bloom’s taxonomy may be helpful to instructors as a scaffolding rubric to help students progress through a hierarchy of skills toward attainment of higher-order cognitive skills, such as applying knowledge and analyzing and evaluating concepts (Athanassiou, McNett, & Harvey, 2003). Instructors may also adapt Bloom’s taxonomy to the skills level of their students, as for example, by assigning to the better students more complex tasks involving analysis and synthesis and assigning more basic

knowledge and comprehension tasks to the weaker students (Lister & Leaney, 2003). As skills of weaker students develop, they too may be challenged with acquiring more complex cognitive skills.”

http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1054875.pdf

As for MI, see this one for its use in Ireland:

http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1017627.pdf

Seems like there are still (mostly constructivist) ed people out there who can’t give it up…

That *is* depressing. Thanks for the links

I’m genuinely interested in the argument and agree about multiple intelligences (as I believe do many after the flush of enthusiasm for them amongst educators some years ago). However, I’m also interested to know how you now feel about SOLO (Biggs, 1982) as a taxonomy. This is something I know well as the assessment framework for assignments at uni, have used and enjoyed experimenting with in my classroom and have read about in ‘The Perfect Ofsted English Lesson’.

Collaborative critical thinking moves understanding forward. Developing critical thinking helps teachers who are genuinely open to it to become more reflective. Therefore, the discussion of taxonomies and multiple intelligences ought to be worth consideration in themselves to support our development as reflective practitioners.

Polite disagreement / ‘caring critique’ / useful feedback / questioning to develop greater understanding – all important for real learners at any age.

What is your current thinking on SOLO taxonomy? Help me to evaluate mine; it is something I have been considering in the context of my classroom recently.

I recanted about SOLO: https://www.learningspy.co.uk/learning/changed-mind-solo-taxonomy/

Thank you. Exploring this link has certainly helped to move my thinking forward again.

Love the comments on Bloom. I am thinking of giving in and buying your new book. There is another issue here that perhaps you address in it? Do we persuade teachers to change their minds, or their practice, by saying their work is ‘shameful’? I think Wiliam is right when he says that teachers typically intend to do good, and that it is very difficult to change their ideas or approach to do something better. This is especially the case if they have tangible successes professionally. I have a deep and abiding respect for many teachers in school, and find it very challenging that many cling to Bloom as if it were a lifebelt. The departure of levels and the need to show progress might help to explain this? More seriously, can we expect to avoid fads in the classroom if we start teachers off with an apprenticeship approach, and then deny them anything except undifferentiated and generic CPD?

Working with new teachers all the time, I think a great deal about how to encourage them to question claims made about teaching and learning. But they also need to respect those with whom they are working and upon whom they depend as a novice. They have a difficult road to follow in schools at the moment…

I’d like to think that my book is much more nuanced than how I tweet. I have been careful to explicitly criticise anyone’s practice or to say that anyone else is categorically wrong about anything. The book is structured so as to ‘soften up’ readers by predicting and explaining the objections that are likely to be raised. You’re right to say that using pejorative language like ‘shameful’ is unlikely to win hearts and minds.

If you do cave in, I’d be gratefe for your feedback 🙂

Caved. Twitter wins again

A model’s a model, not real life. Both here are not accurate representations or real life. They therefore suffer from inevitable imperfections of simplification. Thus, for the purpose above they are simply used as a model and framework to promote enjoyment in learning (not engagement). And what’s wrong with that? How far could or would you want to extend a student at that level in GCSE tsunami study in simply an independent extension? So why not just allow fun for a change? I get that engagement is a myth and all that. But sometimes the fun police don’t need to be called quite so early on in the pursuit of academic and epistemological excellence.

That really is missing the point. ‘Fun’ is a secondary and relatively minor issue (which is why I left it for later.) The purpose of this wasn’t about fun it was about challenge.

A model may be a model. But bollocks is bollocks. And pretending otherwise is professionally disgraceful. There are enough lies and misinformation without endorsing this sort of stuff.

In my opinion there is a lot of missing the point around this kind of thing. I think even Gardner himself would not be too happy about this use of his theory ( read his update at the beginning of ‘Frames of Mind’ – https://books.google.co.uk/books?hl=en&lr=&id=2IEfFSYouKUC&oi=fnd&pg=PR7&dq=gardner+theory+of+intelligence&ots=3-6R2LXNs-&sig=EY6bSGbyTIEVkycQ12wZkOBzcNg#v=onepage&q=gardner%20theory%20of%20intelligence&f=false)

After all MI is a theory of intelligence not a model of learning, just as Einsteins theory of relativity was in essence a theory of relative motion not a model of time travel! All joking aside the world of science and RCTs on which many currently in education wish all to be judged should not also discount sciences other tradition of theorising and debate.

I agree that theories such as Gardner’s should not be presented as fact in ITT or anywhere for that matter, however that should not mean they are not presented at all or that they are presented as “bollocks”. Merely they should be presented as the theories that they are and debated, thereby engaging our profession in a healthy reflective dialogue from the outset.

I think too often theories and opinion are presented as fact in training and especially on social media now and as it would seem within ITT. In my opinion the reality is not that clear cut, the world is not black and white especially in something as complex as learning and teaching.

Should Gardner and Blooms ideas be presented in ITT or anywhere as ‘the way it is’ in my opinion no. (Unfortunately creating such documents as you and @missNQT shared on Twitter implies this is so) However, should Gardner and Blooms ideas be discussed, pulled apart and debated in ITT I think yes. Whether a theory or model is ultimately correct does not mean that there is no value in its ideas.

As a an individual in this profession I think that to take your views as ‘the way it is’ would be just as wrong as to take Gardner’s views on intelligence as ‘the way it is’ equally though I see value in both Gardner’s theory and your opinions. (I’m pretty sure that your intention is not for people to do this with your views as I think you wish to challenge and debate)

Both challenge existing thinking and help shape debate within education and as such I very much look forward to reading your #wrongbook, just as I enjoyed learning about Gardner’s ‘theory’ by going to the source rather than relying on misused, misinterpreted and unfounded extrapolations of his theory.

Hi Dan – Gardener might well be disappointed with how his theory is being used but he has to take some responsibility for such things. It would be helpful if Gardner retracted or recanted his ‘theory’ as being utterly without any kind of empirical base. He never made any attempt to prove it and just because it makes intuitive sense to many people is no excuse for passing it off as a valid theory of intelligence. It isn’t. Not only is it wrong, it’s actively unhelpful in that it’s almost the exact opposite of those theories of intelligence which have a clear empirical base. This seems exactly the sort of thing – along with astrology, Brain Gym and tarot cades – which we should be dismissing as bollocks. The only place it should have in ITT is to explicitly warn students against it.

I take your point and guess Gardner is unlikely to recant his theory as he believes it to be true and, as you know I’m sure, beliefs are tricky things to undo. Maybe it should be his hypothesis on talent rather than theory of intelligence however the central idea that our intelligence may be more than what can be measured in test, empirically validated or not, is worth hypothesising about isn’t it? In terms of the other things you mentioned I would agree they are rubbish but I will keep an open mind about Gardner’s central hypothesis for now. Though I don’t use it directly in teaching, indirectly the idea that our worth should be judged on more than an IQ model of intelligence is worth remaining receptive to I feel. I am sure you disagree and maybe I will change my mind on reading your book.

Hi Dan

Yes of course our worth should be judged on more than just our IQ. Kindness, compassion, wisdom etc. might be far more valuable. This is partly why I object to Gardener hijacking the term intelligence to describe all this other stuff. Being good at a thing is great in and of itself. Branding it as ‘intelligence’ is a sop to the squeamish and a pallid exercise in propping up self-esteem.

Inconveniently, the very robust and empirically validated theory of ‘general intelligence’ suggests that IQ is a very good predictor of other valuable character traits such as leadership, creativity, productivity and motivation. So instead of telling children that being good with plants is just as valid as academic intelligence, maybe we should embrace Dweck’s popular finding that we can all increase our general intelligence (g).

You’re persisting with ‘Gardener’ even though other posters are correctly calling him ‘Gardner’ and tactfully not mentioning it. 😉

That’s what I like about you Gerald: no tact 🙂

Except that the idea of ‘fun’ is not one that is based on the ideas of a some non-academic or anti-academic practitioners and does not reflect the reality for all.

I loved reading – it is one of my first memories as a young child is being in nursery and having a book to read (I probably picked up the habit from mum and having two older brothers already in school). I read voraciously as a child and could not get enough books to read. I wanted to know about – well – everything I could know about. Some were more interesting than others I grant you but still I found it fun reading books.

So telling the child version of me to watch a puppet show would neither have been more fun or more enjoyable. What you are talking about is not objectively more fun for children, it is what that particular adult thinks is fun and it is imposed on children who are expected to also find it fun.

Every teacher has tried an activity with the class or a group that is meant to be fun and yet has been anything but for the children. Each class I have taught has children who have found things fun that I would not have – such as handwriting. It does not make my reading or their handwriting practice any less fun for us as individuals. Imposing generic ideas of fun onto children is lazy teaching and pointless.

I like the top left column heading “.. of killed by Bloom’s [t]axonomy”.

Death by Knowing?

Death by over-analysing.

That should say ‘is one that is based on’

I don’t really understand your critique of Bloom’s Taxonomy.

The taxonomy makes it clear that a strong knowledge base about a subject is a necessary prerequisite for analysis, synthesis, evaluation and creative expression. Surely a correct reading of Bloom’s reaffirms rather than devalues the importance of knowledge in education.

However, if we focus exclusively on acquiring knowledge in a Gradgrindian manner don’t we risk producing a generation of pub quiz champions rather than masterful writers and inquiring scientists?

If we are following your dictum of encouraging students to ‘think hard’ about the material we’re teaching, shouldn’t we make use of useful concepts such as analysis and synthesis to get them beyond basic comprehension? I might know a lot about features of the gothic genre but surely that knowledge is only useful if I can apply this knowledge to an analysis of a text or synthesize my ideas into a coherent argument.

In your bake off analogy, the evaluation part might be relatively easy for Mary Berry compared to the acquisition of years of baking know-how, but surely that doesn’t make it any less important or valuable.

I’m not saying evaluation is less valuable, just that it’s totally dependent on knowledge. Everything is dependent on what you know. Analysing something you know little about is pretty superficial. But nowhere do I suggest that analysis or synthesis is something we shouldn’t do, we just shouldn’t do it first.

Ok, but where does Bloom claim that students should go straight to evaluation or to creativity? Where does he claim that knowledge is somehow less important than ‘higher order thinking skills?

Whenever I’ve used Bloom’s or seen skilled practitioners use it, it’s always been acknowledged that without establishing a strong foundation in knowledge ‘at the base of the pyramid’ higher level thinking skills are difficult to access.

Then you’re more fortunate than I.

Always seen people rushing to ‘higher order skills’ as soon as they can and marginalising mere knowledge. In one school I worked at we were banned from beginning LOs with “To know…”

Strangely that’s exactly what Bloom said. That is also what Anderson and Krathwohl siad when they dealt with some of the issues with the original taxonomy.

But one shouldn’t let the facts get in the way of a good rant. For one who puts som much store by talking the truth, you do still seem to be remarkably reluctant to listen to it.

Interesting discussion though. Thanks

Remarkably reluctant to listen? I doubt there’s much remarkable about my listening skills or lack thereof. You’ve told me something, I’ve listened. I’m not arguing against Bloom himself or any of his collaborators, I’m arguing against the ways in which their taxonomy is routinely misapplied and misunderstood. This is hardly Bloom’s fault, but I do think such taxonomies lend themselves to misinterpretation.

And, as far as I’ve been able to discover, there’s no empirical evidence anywhere to support their theories of how we develop knowledge and learn. If you know of any I’d be gratetful if you could let me know.

Blooms taxonomy, an awareness of multiple intelligences and preferred learning styles, are all part of our toolkit for improving our pedagogy, planning for students’ learning and planning for methods of assessment to find out what students have learnt and already know. It helps us plan for future learning. It actually illustrates beautifully the skill of being a teacher. We try every which way to develop knowledge and understanding from EYFS through to teaching an elderly parent to use an iPad.

It may be inappropriate for a teacher to plan for pupils to write a poem to teach them about the effects of a tsunami but it may be entirely appropriate for a creative pupil to be allowed to present their understanding of the effects of a tsunami for assessment. It is then the teacher’s responsibility to teach the pupil to write in the non-fiction text type (more suited to geography)that the pupil is obviously less secure with.

Teaching is about developing pupils as rounded, independent learners. Whilst we may cater to learning preferences and intelligences to teach and test knowledge, if we wish to develop skills we must support and develop the grasp of all methods of learning and presenting information. All successful learners are rounded; ineffective learners lean heavily to a preferred learning style.

I once received a letter of application from a mature, potential PGCE student; It was in the form of a poem…..someone should have taught him how to sell himself in a formal letter of application!

I love the poem application anecdote! Do you still have it?

You’re absolutely right that “teaching is about developing pupils as rounded, independent learners” and might well be true that “all successful learners are rounded” (although I this depends on agreeing a definition of success) but I’m not at all sure that “if we wish to develop skills we must support and develop the grasp of all methods of learning and presenting information”. This last bit seems a bit more contentious. Would it be appropriate to present information as an astrological chart? I use this example deliberately because there’s no more evidence for MU than there is for astrology; they’re both theories of intuitively explaining the world. What makes Garderner’s theory more respectable?

Bloom’s doesn’t suffer from the quite the same problems because no claims about people’s minds were ever made for it, but it’s still a flawed incomplete way of viewing the process by which we learn. Especially if you represent it as a triangle. Part of the problem might be that we tend to overestimate differences and underestimate similarities. I’ve written about this here: https://www.learningspy.co.uk/learning/overestimate-importance-differences/

I’m not so sure that people really know how they learn anyway. I think it’s a red herring., We can talk about what we enjoy doing, and give anecdotes about very specific things we learnt but nothing more than that. As an example, I learnt the expansion of sin(a + b) = sin a cos b + cos a sin b by saying it to the sound of Big Ben. This does not mean that I learn best when putting information to melody, or specifically the melody of church bells, but it was how I remembered that one fact. I contend that we don’t know how we learn and that we, as teachers, can’t remember learning the stuff we’ve learnt in the first place. There was a time I didn’t know anything about trigonometry, and now there’s a time when I know a lot about it – when did I learn that? How did I learn that? It’s nothing to do with multiple intelligences or preferred learning styles. How I like to challenge my pupils is through testing their deep knowledge – through interesting conversations with them. Why do they thing that? can they explain what they did? Can someone else explain what they did? Does it always work? What if they changed things? Not because they (or I) are auditory learners, but because I’m genuinely interested in hearing them try to articulate their thought processes. I love it when they’ve produce great maths, but they’re not sure how or why.

Personally I think we must encourage NQTs to think of pupils as individuals; To adopt a varied and effective approach to their pedagogy based on their understanding of how pupils make progress in various strands of the curriculum. If the promotion of prefered learning styles encourages the development of effective teaching, and if Bloom’s Taxonomy influences effective questioning, lesson planning and assessment…….I’m all for it! When NQTs don’t understand learning and are given ready made lesson plans as illustrated on the grid you display, I agree, it’s a recipe for disaster……..however it doesn’t mean that the theory behind it is wrong….merely that there is no understanding of it. Hence my Twitter comment that understanding is the foundation for further challenge and development of skills.

Well, that’s fine. I’d argue that you’re entitled to think and believe that as long as you don’t try and enforce it on anyone else 🙂

Oh but I do! 😉

Good grief! I can only hope (I fear in vain) that you don’t have a position of authority in a school. My life’s work is to bend my will against people with that type of attitude

Sarcasm rarely works in text. Seriously though…the more we know about our pupils the better we teach them.

That’s almost certainly true. But it cannot justify perpetuating bankrupt ideas.

I don’t get to read blogs that often these days. I missed your recant on SOLO. Thank heavens is all I can say as I generally enjoy your blogs but became somewhat down heartened when you ‘converted’ to SOLO. We need to return to an understanding that, yes in a sense all children learn differently but just as importantly every subject has its own pedagogy. Some fads fit some subjects better than others. I teach MFL – Blooms and in particular SOLO is next to useless for my subject. VAK on the hand suits us fine. But like all teachers who just try and preserve their sanity we really just play the game. We have a vast array of gimmicky symbols we can use on our power points to demonstrate Blooms, VAK, SOLO, and PLTS. We can only use certain words in LOs. More gimmicks abound with marking WWW and EBI for others it is DIRT and of course the dreaded green ink. All of that energy used to keep SLT off our backs. However it leaves less energy available for real reflection on how well our classes are actually learning. Mastery learning is the new fad – but again I’m ok with that because I think it will work ok for my subject and I won’t waste more time and energy trying to fit square pegs into round holes.

Our biggest problem is organisational. School leaders are looking for the all encompassing generic pedagogy/marking methods so that SLT can scrutinise the teaching that goes on. I understand the need for accountability concerning the spending of tax-payers money but the rapid following these generic pedagogies receive is more to do with the perception that they will help SLT do their job more easily, rather than help support children’s learning. To paraphrase, a member of SLT who oversees my subject, but has never taught it, is entitled to think and believe what they want, as long as they don’t try and force it on me.

[…] followed an interesting discussion on Twitter this week where David Didau lampooned a resource given to @MissNQT at a NQT training event. The resource advocated a variety of […]

[…] When is a bad idea a bad idea? […]

[…] When is a bad idea a bad idea? 23rd June […]

Agree completely. Educators must apply critical thinking when reading, understanding and propagating frameworks. Look at it analytically… understand it’s strengths and weaknesses, so that they use it wisely.

http://purnima-valiathan.com/blooms-taxonomy-an-open-letter-to-benjamin-bloom/

[…] leads to skimming things over and a danger that something genuinely important could be overlooked. David Didau in his blog has warned of the dangers of bad ideas in education and it seems we still have not learned the lessons of the past. I am not for one minute suggesting […]