The exam boards have played their hands and they’re relying on jokers rather than aces. GCSE English literature is a race to the bottom: with the overwhelming concern seemingly being how to retain schools’ business by offering the most predictable, easiest texts.

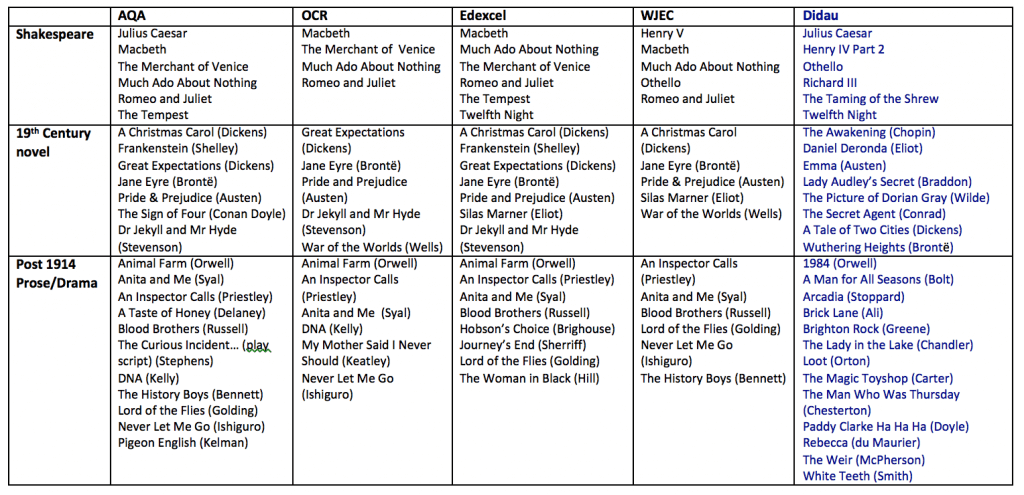

The biggest shock for me has been the suspicious consensus on what constitutes the canon. Every single board is specifying Jane Eyre and Pride and Prejudice, while Jeckyll and Hyde and A Christmas Carol are available on 3 out of the 4’s lists. It’s not that any of the texts are bad – they’re not; I’ve read and enjoyed all of them – but this cowardly uniformity robs pupils of experiencing the broad sweep of literature in English. But more concerning is the unquestioned dominance of Meera Syal’s Anita and Me. This pleasant, but slight text is now clearly considered a seminal work of 20th century fiction. Says who? The exam boards. Why? We have no idea.

Is there a chance to change the boards’ collective hive mind? I don’t know. The argument over presided authors rather than set texts may well have been strangled in its cradle, but can we at least attempt to persuade the blinkered boards to come up with something, anything, more varied and exciting? Maybe not, but as these specifications are still in draft form, I think it might be worth a try.

So, for what it’s worth, here’s my entry into Fantasy GCSE English literature set text lists:

Now, these are just my choices and as such should be open to debate. And in that spirit, here are my justifications:

Shakespeare

My choices are a deliberate departure from the traditionally narrow selection of play pupils study. As such my fantasy specification might well be considered too risky, but here’s why I think these plays should be considered:

Julius Caesar is not perhaps a great play, in that the last two acts are unutterably tedious, but the first three are wonderful. The interplay between the silver-tongued Cassius and the noble Brutus are a delight, as is the pomposity of the doomed Caesar. The tension leading up to the assassination is palpable but things really spark to life in the aftermath of Caesar’s death as Antony vows to let slip the dogs of war and performs possibly the most impressive piece of oratory in the English language.

Henry IV part 2 is knockabout stuff. Amid the epic backdrop of civil war, Falstaff and Prince Hal get up to all kinds of hilarious high jinks, before the future king comes of age and prepares to take up the mantle of leadership and plans to give the French a damn good thrashing.

Othello not only allows us to explore jealousy, loyalty and desire it also presents a non-white character as noble and heroic. Sure, he’s flawed, but his tragic fall into irrationality, jealousy and murder has gravitas and is satisfyingly complex. Plus the oily Iago is one of Shakespeare’s best villains.

Richard III is another excellent bad guy. From his opening soliloquy where he bemoans the dullness of peace to his plaintive demands for horse before his defeat at the hand of Henry Tudor, Richard is unashamedly who he is. Yes this is propaganda, but even when his evil seems caricatured, he is always a compelling character.

The Taming of the Shrew is possibly the most confusing and multi-layered of Shakespeare’s comedies. Is Petruchio a hero or a villain? Does Kate deserve her fate? Is this a play about love or about domestic abuse? There are some wonderful set pieces and the triteness that often concludes a comedy is deftly sidestepped as we wonder whether the shrew really has been tamed.

Twelfth Night treads much more traditional comic ground, but it does it so well. We love to hate Malvolio, and Feste and Jugg can, surprisingly for Shakespearean comedy, be genuinely amusing. We have the cross dressing and confusion we’d expect and it is, of course, utterly implausible. But amongst it all there’s some interesting commentary about puritanism and there are some cracking lines: “Give me excess of it that, surfeiting, the appetite may sicken and so die.”

19th Century novels

For me, one of the biggest missed opportunities in the texts offered by the exam boards is that there is nothing from beyond Britain. Apart from the poetry, this is the only space in the guidelines laid down by the DfE for texts to be chosen from America or elsewhere. It seems appropriate then to at least offer one or two.

The Awakening fulfils this brief whilst also being temptingly short. The story of upper class Edna Pontellier and her Creole friend, Adèle Ratignolle deals with race, sexuality and self-discovery. Written in 1899 this was explosively controversial stuff. It’s a proto-feminist text and therefore invites all kinds of critical perspective and modern readings.

Daniel Deronda is George Eliot’s last and one of her more overlooked and controversial novels but is none the worse for that. Written about Jewishness, Zionism and the treatment of Jews in British society, it shocked contemporary readers. The eponymous Deronda is an idealistic aristocrat who rescues and befriends a young Jewish woman. In his attempts to help her find her family, he’s drawn steadily deeper into the Jewish community and the ferment of early Zionist politics. It’s a tough read, but if you really want to stretch and challenge, this could be the one.

Emma is included mainly because I love Austen and want to offer an alternative to the better known, but certainly not better, Pride and Prejudice. It deals with similar and familiar themes, but this time our heroine is wealthy and secure. She is young, idealistic but sometimes treads heavily on the sensibilities of those beneath her. “Badly done,” as Mr Knightley admonishes her.

Lady Audley’s Secret is like a racier, more exciting version of Hardy’s soporific Mayor of Casterbrige. Braddon’s little known classic contains elements of murder mystery and morality tale but her heroine, the eponymous Lady Audley is always compelling. The plot is a roller-coaster of twists and turns and is easily as good a yarn as anything penned by the more moribund Dickens.

The Picture of Dorian Gray is a bit of an outsider. When compared with the others on this list I don’t think I’d chose it, but it’s worth including for several reasons: Wilde as about as British as it’s possible for an Irishman to be, but he’s still Irish; it has a well-established pedigree as a gothic classic, and its length makes it a tempting alternative to some of the brief offerings such as Jeckyll and Hyde or Sign of Four.

The Secret Agent is my favourite Conrad novel. He’s an interesting choice in that he wrote in English but was a native German speaker. This outsider status allows him to comment on the anarchist ferment and xenophobia rife in the London in which his novel is set. Probably wouldn’t sneak through as it was written just after 1900.

A Tale of Two Cities – For those unable to conceive of the 19th century novel with a bit of Dickens, why not give this one a go? From the classic opening lines (It was the best of times, it was the worst of times…) onwards this is high octane storytelling Set between Paris and London in the build up and maelstrom of the French Revolution, this is a love story played out against the menacing shadow of the guillotine.

Wuthering Heights – What better antidote to the simpering Jane Eyre than the confusing gothic sprawl of her sister’s windswept and wild tale of love and revenge played out on the lonely, savage moors? Heathcliffe and Kathy are every bit as star struck and ill-fated as any iconic literary couple and this is a novel that deserves attention as much as an other.

Post-1914

We may well be limited to writers originating from the British Isles (including Ireland) but that leaves thousands of marvellous texts from which to choose. I think it’s a shame that we have to go for either a novel or a play, because my personal preference would always be for the richness and depth a novel can offer, but there you go.

1984 – Orwell is one of the finest prose stylists in the English language and as such very much deserves to be studied, butt’s maddening that whilst Animal Farm is offered by 3 of the 4 boards, nowhere is this dystopian classic available. This novel still permeates popular culture and pupils are always excited to recognise the origins of Room 101 and Big Brother.

A Man for All Seasons – Robert Bolt’s wonderful historical play depicts the rivalry of Moore and Cromwell, the capriciousness of Henry VIII and gives life to the big religious questions of the day. I studied this myself at school and loved it; if I was forced to choose a play over a novel, this would be it.

Arcadia – Or would it? This is, for my money, Stoppard’s masterpiece. There is so much humour and sadness as comedy and tragedy collide in this country house farce about life and death. The opening, set in 1809, captures something of Oscar Wilde and the jarring shift to 1990s realism allows for some ferocious social commentary. I’m not sure this works as well at GCSE, but it’s thrilling theatre.

Brick Lane – If you want to study a fabulously well-written novel by a female British Asian novelist, why would choose Syal? Monica Ali’s book is better. It just is. The story follows two sisters; Nazneen ripped from everything she knows in rural Bangladesh and trapped in a joyless arranged marriage with a much older man in a high-rise block in London’s East End, and Hasina who elopes only to be forced to face the brutal realities of life. It’s hard-hitting stuff and is guaranteed to provoke a response.

Brighton Rock – I ummed and ahhed about which Greene novel to include, but never for a moment did I consider not having a Greene at all. My personal favourite is Our Man in Havana, but the enduring appeal of the violent but secretly sensitive Pinky’s wild romp through Brighton’s seamy underbelly still works really well today.

The Lady in the Lake – Does Raymond Chandler count as a British writer? Possibly not, but if there’s any way we could shoehorn onto a list, he’s definitely worth having. He raises the detective beyond the confines of genre fiction and writes stunningly evocative prose. For me this is the best plotted, most satisfyingly complete example of his oeuvre.

Loot – Joe Orton’s dark farce is a comic masterpiece and follows the fortunes of two blundering young thieves, Hal and Dennis, as they hide the proceeds from a bank robbery in the coffin of Hal’s recently deceased mother. The play is a biting satire on bereavement and public perceptions of the police force with regards to laws and corruption, but it’s mainly included for variety – I’d never plump for it over Bolt or Stoppard.

The Magic Toyshop – One of Carter’s best novels, this is a classic coming of age story but with some very weird twists. Following the death of her parents, 15-year-old Melanie is sent to live with her callous, uncaring uncle in his London toy shop. The prose is crisp, the characters are brilliantly drawn and story will resonate with pupils.

The Man Who Was Thursday – I’ve only recently read this following a recommendation from Martin Robinson. And having read it, I love it. Chesterton is bafflingly neglected, and this book is a throughly approachable way in. It wears the trappings of a detective novel, but it’s really about life and creation itself. I’m not sure whether it would technically be allowed as it was first published in 1908, but surely an exception could be made? The bizarre decision to marginalise texts written between 1900 – 1914 also makes EM Forster persona non grata! If I can’t have it I’ll do for Hartley’s The Go-Between instead.

Paddy Clarke Ha Ha Ha – Irish writer, Roddy Doyle’s Booker prize winning tale of the break up of young Paddy’s family is compelling told through the eyes of a 10-year-old boy with a heartbreakingly incomplete understanding of the world. It’s structure is confusingly non chronological but still manages to trace the passage of time in a pleasing rites of passage.

Rebecca – Why isn’t this book read in school? Maybe it’s a question of length? It’s a wonderfully noirish, darkly gothic rags to riches tale that consciously echoes Jane Eyre. The story is told by the unnamed second wife of aristocratic Maxim de Winter, but it;s his dead first wife, Rebecca that haunts and permeates this compelling book.

The Weir – Connor McPherson’s play is set in pub in rural Ireland. The characters tell ghost stories based on Irish folk-lore which reveal their character and build up to a narrative about loneliness and missed opportunities. It’s a subtle play and not for everyone, but its intriguing structure and expertly crafted dialogue make it worthy of study.

White Teeth – If you feel the need for something urban, multi-cultural and modern (and don’t fancy Brick Lane) you do worse thank consider Zadie Smith’s debut novel. Dealing – among many other things – with friendship, love, war, it follows the fortunes of three cultures and three families over three generations. It’s warm, funny and very well-written.

So, these are my choices. What are yours?

Here’s Jonathan Peel’s list and here’s another from The London Oratory School.

I want to teach your spec!!! At my school we’ve taught ( for GCSE controlled assessment) Far From Madding, Tess, Portrait of Dorian and Pride and Prejudice – all the students loved the experience – but many found it hard at time: in retrospect they all say it was best bit of the course. I’d include some Hardy, FFMC works so well with teens. It has story and heart. I also just need to teach Macbeth and JC is dreary by end so I’d fight you on that one! . I’d compromise on Ant and Cleo. Deronda is way too hard for 15 yr olds- great for A level though. Braddon? Oh please… If only. Wish teachers had more input!

Thanks. Can’t work out whether you’re being scathing about Braddon?

Not scathing! Adore Braddon’s ‘ Lady Audley’s secret’. The whole idea of a beautiful woman as villain and the links to French Lit are exciting stuff. I try to teach extracts from this novel as Unseen at AS and students always go off to read the rest!

The last sentence of Brick Lane is one of my favourite final lines. I’d have Dracula on my list and Rasselas, too.

Rasselas might be too early to qualify as it’s 18th century. Otherwise I’d be tempted to do Tristam Shandy 🙂

And Dracula is a pet hate!

Thanks, DD

Hmmm, Rasselas wouldn’t fit in the spec. Well, we are talking fantasy. I’d consider Wilkie Collins (The Moonstone). I enjoyed Orwell’s Keep The Aspidistra Flying, A Clergyman’s Daughter and Down and Out In Paris and London as a teenager. Tess of The D’Urbervilles, perhaps. Merchant of Venice. I love your idea of having some Joe Orton: a very funny writer. When you think of all the breadth that is out there and then what the Boards have chosen, it just sees like a lost opportunity.

One Shakespeare is would have is Titus Andronicus. It’s sheer passion, violence and humanity drips from the pages. To grab pupils attention this is the one for me. The best work about vengeance .

I did consider Titus – but what about all the rape? Suitable?

Surely we should use our “fantasy” literature in Y7,8,9. Get the exciting, juicy stuff in there and get them hooked early on. If they aren’t really engaged with or excited by reading in Y10, it’s going to be a struggle regardless of the text.

Of course we should. I’ve written about this here: https://www.learningspy.co.uk/english-gcse/principled-curriculum-design-teach-english/

I’m a great fan of science fiction, or speculative fiction as Margaret Attwood calls it. What about Farhenheit 451? Also an example of something less dystopian if not actually utopian Dune by Frank Herbert perhaps. The i Robot stories by Asimov are classic sci fi, and raise all sorts of interesting questions. But probably neither Herbert nor Asimov can be considered great literature. And I wonder if somewhere students should be required to make a personal book choice and then have a question to answer about it. Probably difficult to manage but may be worth exploring.

Re: The Man Who Was Thursday, here is an audio of Will Self talking about the novel: http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p0192qdm

[…] Wanna play fantasy GCSE Literature specifications? […]

[…] Read more on The Learning Spy… […]

Chandler is fantastic; I wonder if you would see merit in following him up with a fellow transatlantic Old Alleynian, PG Wodehouse? Compare and contrast the equally wonderful use of language and convoluted plotting used to very different effect…

How about Gaskell’s North and South? A powerful novel. (I disagree that Jane Eyre is ‘simpering’: each time I go back to the novel I find her more complex and darker.)